The dwindling momentum for NYC property tax reform is being exacerbated by the coronavirus crisis and adjacent economic disaster, according to a recent report in the Gotham Gazette. An advisory commission convened by the Mayor and the City Council to assess and reevaluate the city’s “confusing and unfair” property tax system released its long-awaited recommendations back in January, but the growing pandemic stalled the intended community conversations and legislative proposals to follow.

Initially formed as a next-ditch effort to address what many see as an antiquated, opaque, and inequitable jumble of assessments and levies that overburden lower-income communities and communities of color, the Advisory Commission on Tax Reform is now in a holding pattern while city and state officials grapple with issues of logistics, prioritization, and a virus-fueled financial crunch.

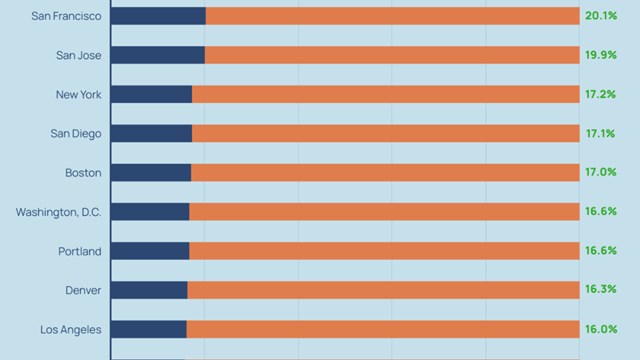

However, as the Gazette indicates, the communities hit hardest financially and health-wise by COVID-19 are also disproportionately taxed in the current system. According to the report, “Homeowners in some of the city’s most booming neighborhoods have among the lowest effective property tax rates, as do some of the most expensive co-ops and condos, while homeowners in places like the Bronx and Staten Island, which have not seen rapid gentrification, pay a much higher percent of their property’s value in real estate taxes. Tenants often serve as a release valve for the high taxes on large rental buildings.”

The January recommendations focused on inequities in the assessment of one- to three-family homes, small rental buildings, and cooperatives and condominiums, sparking a range of reactions around the real estate industry. The first of a series of public hearings was set to take place in Staten Island on March 12, but with the pandemic taking hold in New York and surrounding areas at that time, the session was cancelled.

And now, with the city's budget filed on July 1 and a $9 billion budget deficit looming, expedient reforms to the system that garners such a large percentage of city revenue—35% for the current fiscal year, according to recent estimates—are not likely. New York City “relies on property taxes to fund the essential city services like hospitals and our first responders,” says Laura Feyer, a spokesperson for Mayor de Blasio, pointing to the conundrum in addressing a burdensome property tax system during a pandemic.

The Mayor himself echoed that proposition on May 10 to reporters who asked about property tax relief for struggling homeowners and landlords: “Especially since we don’t know what’s going to happen in Washington,” said de Blasio, “we right now are absolutely dependent on whatever resources we can get, and property tax is a part of it for sure.”

On the other hand, New York City fiscal watchdogs and reform groups say that the pandemic has made addressing inequities in the property tax system is more important than ever, and a growing chorus of landlords, tenants, and business owners are calling for property tax relief as the economic fallout knocks on their doors. “The time should not be wasted,” wrote Andrew Rein, executive director of Citizens Budget Commission, a nonprofit watchdog, in an email to Gotham Gazette. “The Commission’s report was a solid start to comprehensive reform.”

Similarly, Martha Stark, former finance commissioner under Mayor Michael Bloomberg who now serves as policy director of the advocacy group Tax Equity Now, said in an interview, “Given that the city’s only mechanism for raising revenue is going to be through the property tax, I don’t know how much more urgent it could be to ensure the taxes are done in a way that is fair and that is really reflective of people’s values.” (Tax Equity Now has sought to reform the tax system through the courts; it filed a lawsuit against the city and state that was a catalyst for the formation of the advisory commission in the first place. That lawsuit was dismissed in the appellate division earlier this year, according to the Gazette, but the group is filing an appeal in the state’s highest court.)

However, changing New York City’s property tax scheme requires action at both the city and state levels. Over the past 40 years, the Gazette notes, conflicting interests in those arenas have put a wrench into any meaningful reform. Now, while the city strains to shore up its budget, the state has put property tax reform on the back burner. “Property tax reform is not the issue we are dealing with this year,” said State Senator Brian Benjamin, a Manhattan Democrat and chair of the Committee on Revenue and Budget, on a recent podcast. “At this point we are really dealing with the COVID crisis.”

Comments

Leave a Comment