Walking on the sidewalks of New York can be tough; you need to maneuver through streams of pedestrians chatting away on their cell phones, many walking right at you from the opposite direction, and you need to be focused on what’s in front of you.

After all, many of the buildings in New York are old, and through the years there have been numerous cases of debris falling from deteriorated facades—damaging cars, injuring—and in some cases even killing—passers-by.

For those reasons, New York City enforces a number of façade-related regulations. The most important of these is Local Law 11 of 1998, which mandates regular inspections of building facades to make sure they’re in good shape. There are approximately 12,500 city buildings subject to the inspection requirements of Local Law 11.

A Little History

To understand Local Law 11, says Alan Epstein, a licensed professional engineer, attorney and president of Manhattan-based Epstein Engineering PC, you need to first look at its predecessor, Local Law 10 of 1980. LL 10 was New York City's initial façade inspection law. It was signed into law by then-Mayor Edward Koch on February 21, 1980 and was praised for what it did.

“It was enacted in the aftermath of a tragic accident in which a very large piece of debris fell from the façade of a building, striking and killing a woman on the street,” Epstein says. “After that the City Council passed a law requiring the front façade (or street level facades) of buildings greater than six stories in height be inspected every five years visually by a licensed professional engineer or a registered architect.”

For 20 years, LL 10 was the standard that everyone had to follow, so every five years the street facades would be inspected to protect the public from objects that could fall.

“After the inspections, there were obligations on the part of the property owners to repair conditions that were revealed and documented in the inspection report,” Epstein continues. “At the end of 1997, an accident occurred on Madison Avenue, where the back portion of the building collapsed, taking with it part of the front of the building, and out of that came an awareness that it was not sufficient to merely inspect the facades above the street.”

The belief that it would be prudent to inspect all of the facades led to the ratification of Local Law 11 in 1998. There were two primary differences of the new law, which superceded Local Law 10: One was that all of the building facades would now be inspected—not just the front. Additionally, an inspection would also be performed on one of the street facades from a scaffold or moving platform.

Inspection Time

Local Law 11 functions on a five-year cycle and apples to all buildings greater than six stores of height, and that includes all commercial, residential, co-ops, condos or hospitals. It applies only to buildings in New York City; it does not apply to buildings on Long Island, New Jersey or Westchester.

“When LL 10 was first passed, everyone was supposed to have been checked and inspected by February 1 of that year—but no one knew about it in time, so there was a two-year window to get it done,” says architect Howard Zimmerman. “Every building would need to be inspected every five years.”

As of 2010, which is considered the seventh cycle of the inspections, the Department of Buildings has changed the schedule in order to stagger the buildings. Depending on the block number of the building, the next window of inspections could be from February 2010-February 2012 or from February 2011-August 2012 or from February 2012-February 2013. This will make it easier for the Department of Buildings to process the approximately 12,500 inspection reports over a three-year period.

For condos or co-ops that fall under Local Law 11 requirements, it’s important to seek out a qualified architect or engineer to perform the inspection and write out a report.

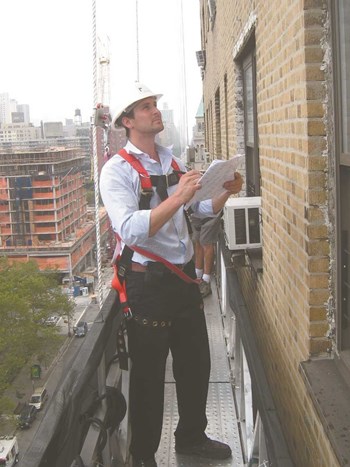

“The typical inspection is a visual survey of everything,” says Stephen Varone, AIA, of Rand Engineering & Architecture P.C. “You check all four facades, looking at anything that can potentially be a hazard of falling down to the street. Plus, the law requires at least one scaffold drop from the roof to the ground, on the street-facing façade. Typically that involves a 20-foot-wide rig.”

According to Rand, new inspection requirements are now in effect. Facade inspections must be conducted, witnessed, or supervised by what the DOB calls a "Qualified Exterior Wall Inspector." QEWIs must be either a New York State registered architect (RA) or a "New York State licensed civil or structural professional engineer" (PE) with at least one year of experience. In previous cycles, the person filing the facade inspection report could be either a New York State registered architect or any New York State licensed professional engineer—the PE did not need to have a civil or structural engineering degree.

Because of this change, professional engineers who have filed Local Law 10/80 and 11/98 inspections in previous cycles but who are not civil or structural engineers (for example, mechanical engineers) will no longer be permitted to file these inspections reports. (In practice, New York State grants only one type of licensing for professional engineers—the PE license does not note the engineer's area of specialization.) Tradesman, contractors, and other technicians, however, can still perform inspections (but not file the reports) under QEWI supervision.

The visual component is usually done with binoculars or a camera with a telephoto lens. Before the inspection begins, a sidewalk shed must be erected to protect pedestrians passing underneath. An engineer or architect may also get into a building across the way to see the building being inspected from a better angle or use a fire escape to examine the building more closely.

“If what you see if inconclusive, more drops can be arranged,” Varone says. “If an inspection uncovers some sort of deterioration or some type of defect that you can’t see on visual interpretation, then you would call for probes and investigate.”

Next, the building must comply with having a section inspected more closely, done with the use of a scaffold.

As a byproduct of Local Law 11, there’s an emphasis on repairing leaks or water penetration, because water is known to cause the kind of structural defects that could lead to materials falling from the facades.

In the Report

According to Zimmerman, there are two possible outcomes from the inspection. If there’s nothing that is an immediate hazard to the public, the building may be declared “safe with repair and maintenance.” If conditions are found that pose an immediate threat to the public, it’s considered in “unsafe” condition.

In the latter, building owners or administrators are required to put up a sidewalk shed immediately and have 30 days to fix the condition or give the city a plan of what has been done to try and get extensions, which can buy them 90 additional days at a time.

“If you find conditions that are not unsafe, which are called 'safe with repair and maintenance,' what that means is that I can’t guarantee that these items I've listed have five years left in them before they become unsafe,” Varone says. “You put a date on there, anywhere from two to four years, and what needs to be done, and you set the timetable.”

The owner is supposed to comply with that timetable laid out by the engineer's report, but depending on the time of the next inspection, they may elect to wait.

“If you did an inspection in 2010 and you listed a bunch of stuff to finish by 2013 but the next report isn’t due until 2015, the city is not aware [of the recommendations],” says Varone, “so there is a gray area where you may not be compliant, but the city hasn’t caught you yet. If by the next inspection those items aren’t done, it would be considered unsafe.”

A sidewalk bridge is erected and placed to provide temporary protection for the public until the completion of all repairs, and bids are taken and a contractor is selected to do the work.

“A residential building will contact or retain an architect or engineer to perform their inspection and file a report. The professional is required to review the prior Local Law 11 report,” Epstein says. “If it’s found that the conditions from the prior report are not repaired, those same conditions are now classified as unsafe in the new report.”

Paying the Price

There are a number of violations associated with Local Law 11 and failing to comply will lead to fines and further sanctions from the DOB.

“The first is failing to file a report,” Epstein says. “If a report is not filed in the designated time frame, a violation will be issued and it will be accompanied by a fine. An engineer or architect retained by the building files the report with written authorization from the building.”

The fine for not filing a report on time or having an unsafe condition you haven’t responded to starts pretty small, according to Varone, and has gone up from $150 to $250 a month. “It’s $250 a month. The DOB talks about criminal penalties as well to use as a threat, but of course owners sometimes do the math and pay the fine for a few months so they can start the work in the spring and don’t have to pay to have a shed up all winter.”

There can also be Environmental Control Board issues and fines—and those can lead to multiple violations as time progresses.

“A second series of violations pertain to buildings with unsafe conditions,” says Zimmerman. “If conditions are not repaired within appropriate time frames, violations will be issued and assessed appropriate fines. You can get multiple violations for the same infraction. Usually the worst is if you get a violation and ignore it and it goes into default status because you missed a hearing.”

Before any repair work can begin, permits are needed from the DOB. If your building happens to be a landmarked building, it requires one from the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) as well.

“This is time consuming, so from the time of inspection to work beginning can often be many months,” Zimmerman says.

Final Thoughts

Surprisingly, there are no façade laws for buildings six stories high (without basements) or lower.

“The law requires all owners to keep all buildings in good condition—but that’s a general statement and there’s no filing required,” Varone says. “Enforcement is weak and the compliance is weak because there’s no one looking at the building to see if it’s really in good shape.”

Other similar laws have been passed in other cities—including one in Philadelphia just last year—that have at least considered or implemented lowering the height requirement. But in the meantime, for the sake of building residents, visitors, and passers-by on the street, part of every board/management team in the city's responsibility is to make sure their building's exterior is LL11 safe and compliant.

Keith Loria is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor toThe Cooperator.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment