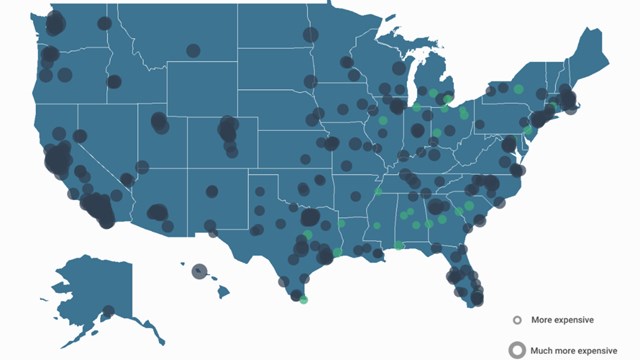

Even before the COVID-19 crisis hit, the question of where real estate values were going was the elephant lurking in the corner of the room. Some submarkets (like Florida, for example) were strong—and getting stronger. Others (like New York City) were suffering declines—primarily thanks to tax law changes passed back in 2017. The limitations on deductibility of state and local taxes had already had a deleterious effect on co-op and condominium prices in New York City, its suburbs, and nearby New Jersey, which are all high-tax areas. Other factors, like the change to the so-called ‘mansion tax,’ also contributed to a decline in prices and values in New York, as did substantial overbuilding in the high-end luxury market.

Then along came COVID, and its accompanying economic shutdown—which has changed the realities of work and lifestyle, perhaps permanently to some extent. Are brick-and-mortar office spaces as essential as they once seemed? Can businesses such as law firms, advertising agencies, even financial institutions conduct their daily operations without a physical space in which personnel can congregate? If not, will an urban lifestyle be as appealing as it once was, particularly if the attractions of that lifestyle—dining out, theatre, nightlife, and the rest—are sharply limited, or fraught with anxiety?

What Does the Future Look Like?

David Eisenbach is a historian, author, and lecturer at Columbia University, and is an expert on urban history, particularly that of New York City. He sees huge potential changes coming. “Density is what makes New York—and maybe breaks New York under COVID-19,” Eisenbach says. “Just look at the subway. If you think flying exposes you to COVID, think about a 40-minute subway ride with a transfer in Times Square during rush hour. Or what about the packed elevator to the 30th floor of your office building, every day, twice a day, five times a week? Density is what fills New York’s universe of restaurants, clubs, and theaters every night, making it the hotbed of cuisine, culture, and entertainment that it is. But what if nothing’s open? Or the experience of sitting in a restaurant or theater is stressful? What if great New York pastimes like window shopping or rambling through Central Park are now anxiety-provoking?” New Yorkers are often quick to counter complaints about the cost and hassle of living here with examples of all the amazing things one can do and see here, and nowhere else. But, says Eisenbach, “With all the frustrations and expenses of living in New York City, what happens if there are no perks?”

Eisenbach points out that a big test of the durability of urban lifestyle will be whether schools can reopen in September. “No decision has been made,” he says, “but it’s not looking good. If offices and schools aren’t open, or if your office allows telecommuting, there isn’t much need to live in New York City.” And if that’s the case, a major reshuffling of residential properties may be on the near horizon.

The Possibility of a Rebound

Alternatively, “The default assumption by most is [that the pandemic will have] a negative impact,” says Jonathan Miller, principal of Miller Samuel, a national real estate appraisal and advisory firm located in Manhattan, “but there is literally a shortage of empirical evidence for that assumption—and until the New York brokerage community is allowed to physically show property, we won’t have that evidence. I suspect there will be a surge of contracts at that moment, and from that point on, we will see price discovery.”

Miller does report, though, that “[s]ince we are in the middle of a global pandemic and are overwhelmed with uncertainty, there is already more outbound migration in the ‘city-to-suburban’ narrative.” Many city-dwellers with second homes have become COVID-19 refugees, fleeing the city for exurban areas like the Hamptons on Long Island, the Hudson Valley, the Berkshires in Massachusetts, and New Jersey’s shore and horse-farm country. There has also been an exodus of young families to both nearby suburbs and distant destinations, where managing children is easier.

Overall, though, Miller says he sees the market recovering easily. He indicates that market factors affecting the value and pricing of apartment homes had begun to settle into some sort of natural equilibrium before the COVID-19 crisis. He expects that trend to continue once the real estate transaction process can resume.

On a Micro Scale

So what does this uncertainty mean for co-op and condo owners and, by extension, for how boards make their decisions in regards to sales of units? Condominium boards have little grounds upon which to reject a prospective purchaser, other than the purchaser’s inability to meet financial obligations. In co-ops, though, boards have the power to reject a sale for any reason, or for no reason at all.

According to Miller, “The heavy layer of uncertainty all of us are grappling with makes boards more conservative in their decisions. It is the same outcome seen in the lending community as they continue to mitigate risk through more conservative LTVs [loans-to-value], higher credit scores, and enjoying the spread by not letting rates drift much lower.”

The question is whether a board can choose to reject a sale on the grounds of wanting to maintain a particular price level within the building. According to Phil Simpson, an attorney with Robinson Brog, a law firm based in Manhattan, “Co-op boards do just that. Their reason or justification—never put into writing, of course—is to protect overall value in the building. Remember, they do not have to give reasons for their decision to reject a purchase; they just cannot violate the anti-discrimination laws of New York City and New York State. People may find it hard to sell, even if their expectations of a sale price have adjusted to the market, because boards may not approve sales because of that price [being too low].”

An Experienced Manager’s View

Daniel Wollman, CEO of New York-based management company Gumley Haft, says, “In 30 years of managing co-ops and condos, I have seen no more than a couple of rejections on the basis of price. It’s not common. Purchase price is certainly something a board would look at, because their job as a fiduciary is to help build value—but each building has its own financial criteria. Co-op boards look at an application, analyze it, apply their building’s criteria, and then determine whether they need more information, whether they want to interview the applicant, or if they will reject the proposed purchaser. If for any reason a board believes that they want to reject the proposed purchaser, they would typically decline to interview them. We tell our boards that if they are not prone to approve the application, they should not go forward with the interview. That is generally accepted advice by legal and management consultants.”

Wollman goes on to say that “[t]he market is going to reset. Buyers and sellers are going to reset their expectations along with the market. I don’t think people are going to dump apartments way below market. I don’t see that happening. I don’t think people want to get out of Manhattan that badly. People will wait for the market to settle down. And then, if they want to get out of New York for other reasons than COVID-19, they’ll sell their apartment. Do I see people running away from New York and selling their apartment for any old price? No. It’s a waiting game, and the market will rise again in time.”

In the meantime, the consensus among market-attuned pros is that boards of both condominium and co-op properties should proceed with rational, business-judgement-driven decision making, rather than reacting to rumors or unsubstantiated hunches. That’s not only the best way to survive and thrive past the current crisis, but good advice even in calmer times.

A J Sidransky is a staff writer/reporter for The Cooperator, and a published novelist.

Leave a Comment