Do you remember when you were a kid and the closest thing you had to a cell phone at the time was two cups with a string attached between them? You pulled the string taut, spoke into one cup, and hoped your friend holding the other would hear you. Miraculously, they did! That long-ago game worked because sound travels along rigid pathways. If you let the string between the cups go slack, the sound doesn’t travel. Turns out, all you really need to know to understand soundproofing you probably learned in kindergarten.

The ABCs of Sound & Soundproofing

According to Sarah Marsh, President of MAAI Marsh Architects in New York City, “There’s no such thing as soundproofing; rather the proper term is sound attenuation.” Sound attenuation is the effective reduction of sound—not necessarily its elimination.

Much of the sound we hear through walls and ceilings in our apartments is known as structural sound, explains Marsh. Structural sound is created inside a building by someone or something causing vibrations. “The only way to stop the vibrations is to interrupt them with a sound isolator,” she says. “Examples of sound isolators are a rubber gasket or a huge spring.”

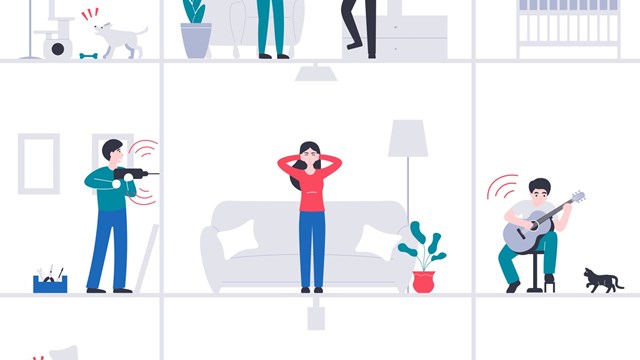

Alan Gaynor, an independent architect based in New York, adds that noise in multifamily buildings can be further divided broadly between two general categories: airborne noise and structural noise. Airborne noise filters in from adjacent units and outside. It includes things such as music from a stereo, raised voices, or the rumble of the garbage truck at 6:30 on a Saturday morning. Structural noise—the negative aspect of structural sound—is the reverberations that come through the actual building structure, as Marsh described above. The reviled ‘footfalls’ of your upstairs neighbor’s children or high-heeled shoes clacking against the floor at the same time every morning are the essence of structural noise.

Solutions for these different types of noise vary in approach. In reality, the underlying science behind the solutions is pretty much always the same: relax the string.

An Unintentional History

Urban multifamily housing can be divided into three basic categories as far as sound is concerned. The first period stretches from World War I through the pre-World War II construction boom, and then on to the mid-1960s, when construction methods began to change for both economic and technological reasons. The second period covers the years from the late 1960s through the early 1990s. The third period begins in the 1990s and brings us to the present.

Older buildings, often referred to as prewar, were heavier, built with more layers and solid materials. “Sound was less of an issue before World War II,” says Gaynor. “Buildings had plaster walls, used gypsum block, and [had units with] high ceilings. They also used lots of concrete fill, which is like rubble, so it’s pretty quiet. There are many layers.”

According to Kevin White, Owner of Brooklyn Insulation and Soundproofing, which has offices in New York and New Jersey, “The old buildings were soundproofed by density. Everything back in the day was built solid, and extremely dense. The denser the floor or wall, the harder it is for that sound to transmit through.”

Mid-Century Change

From the late 1960s onward, however, “builders went for lighter-weight materials like sheetrock and studs, so you have much more sound transfer,” Gaynor says. This has led to more issues with both airborne and structural noise.

According to Marsh, the level of noise in a building “has to do with math. And developers aren’t using math in their projects. They build as they do because they can,” she says. “It’s all about the cost of the materials. A lot of developers on less high-end projects won’t put in expensive materials. Consequently, there’s a poor quality of sound control.”

White concurs. “We see how fast developers are putting up new buildings, and with soundproofing it’s about quantity, not quality,” he says. “We see cheap materials that aren’t installed correctly in new units, and sometimes they don’t do anything to decouple the floors, which is bad for impact transmission.”

White also notes that “with people working at home because of COVID, we’re receiving a lot of calls about buildings that have concrete decks—which you figure would be soundproofed, but people are getting sound transmission through the concrete. To correct the problem, we anchor in a new ceiling grid—basically a support system to hold a new ceiling—and decouple it, so it acts like a shock absorber and reduces the noise that’s traveling through the concrete.”

The proliferation of glass residential buildings over the past two decades has made sound problems both more common and more acute. Glass does not act as a sound reduction agent in any way. Many new buildings are constructed with shared walls between units, as well as between units and common areas, which adds to the likelihood of both airborne sound infiltration and structural transmission.

Solutions

So, back to the cups and the string. Dr. Bonnie Schnitta, a national expert on sound and president and owner of SoundSense, a national acoustical consulting and engineering company, says, “If we’re talking about a wall, a floor, or a ceiling, there are certain things that improve or are successful in inhibiting sound. The criteria are that it has to be dense, must have some level of flexibility or resiliency to it, and has to have a complete seal. You can have the best wall in the world, but if it’s got a hole in it, it’s not going to work.”

The culprits when it comes to sound transmission between apartments are often single studs and back-to-back electrical outlets, which do little to reduce or interrupt the flow of unwanted noise. Though strongly cautioned against by architects, developers will often ignore these pitfalls for the sake of saving a bit on construction costs.

Gaynor adds that “some soundproofing materials are used within the initial construction, and some installed after. The easy ones are after construction—things like carpeting and curtains. Resilient underlayment is used in floor construction to reduce sound conduction. It might be foam or fiber. It could also be roof felting, cork, or rubber.”

Schnitta agrees, but cautions that “a thick poured concrete floor itself is great for stopping sound, but if it’s not thick enough, it will be terrible for footfall,” or anything else with an impact on the floor, such as dropped articles. She explains that in New York, there is a required minimum Impact Insulation Class (IIC) for newer buildings. “Many old buildings were not subject to this requirement. The requirement to cover 80 percent of your floor with carpet was enacted to account for this, but if it’s not the right carpet or padding, it won’t solve the problem. There is a special carpet pad called Vibramat that is very effective for this. It raises IIC by 20 percent.”

Along with Vibramat, Schnitta explains that there are many other sound-stopping options today. In new buildings, she recommends loaded vinyl as a means to reduce sound transference through studs. “It’s impregnated with non-toxic metals, and it’s dense to add flexibility,” she says. “This doesn’t contain lead—remember lead walls?—which they used to use. This vinyl has a better transmission loss factor than lead to eliminate sound, and it’s only an eighth of an inch thick.”

But what if your building is already very much built, and the sound just keeps on coming? Marsh suggests that you could put up a false wall between your place and the next apartment, which could cost you a few square inches of space, but might be well worth it for a good night’s sleep. Or you could build a closet along the offending wall and use it to store clothes and toys, which are sure to absorb the sound. She relates one client whose neighbor had a very regular schedule for his “personal life.” Saturday morning comes once a week, as the adage says. The neighbor was like clockwork, and very noisy. Marsh suggested adding a false wall, which would have absorbed the sound. Ultimately, the client chose to do nothing. Perhaps the neighbor changed his schedule.

What’s New & Improving?

“More innovative sound control products have been patented in the last few years than ever before,” says Schnitta. “Where before there wasn’t a solution, now we have one. A good example is a type of pad that if you put this down before you pour concrete for a foundation, it will even inhibit subway noise if there is one nearby. Knowing that resiliency is an important piece of the solution set for walls, there are new clips that have neoprene pads integral to the design to prevent connecting drywall to channel sound. Also, a lot of attention to acoustic leakage points like wrapping the backs of outlets helps. An acoustic muffler will inhibit sound from coming through recessed lights that are not fully insulated cans.”

Another new patent is known as an eaves muffler, notes Schnitta. It’s a special acoustic plate that is connected to a diffuser or vent with a one-inch space between it and the ceiling or wall. Its purpose is either to inhibit mechanical noise that comes through vents, or inhibit sound going room to room, or apartment to apartment through different conduits and vents. “Essentially, [it eliminates the effect] of hearing people in your bathroom from an adjacent apartment.”

Another new product noted by Gaynor is sound attenuation paneling for floors and ceilings. “They are quite attractive,” he adds. “And they are effective. I’m using them in some of my current assignments.”

Clearly, when it comes to shutting out the clamor, every little bit helps.

AJ Sidransky is a staff writer/reporter for CooperatorNews, and a published novelist. He can be reached at alan@yrinc.com.

Leave a Comment