As we sit in our buildings all over the city, we'd like to think that we're protected from emergencies by our sprinkler systems, electronic alarm systems and staff. However much we don't want to think about it, an emergency situation can happen, and your building should be prepared.

Because condo and co-op buildings in the New York metro area can vary so much, from the spread-out suburban-style condo in Long Island or eastern Queens to the landmark high-rise on Central Park West, making an individual, customized disaster plan is a must.

The best place to address a customized emergency plan is at a board meeting. Putting emergency planning at the top of the agenda, however, might be a tough sell in some buildings because many residents are more concerned with day-to-day happenings.

James Freeman is a man who is familiar with all kinds of apartment buildings—he's both the president of the Inwood Tenants Association and the president of his co-op board on Park Terrace West. "The number one priority for a board," he says, "is to focus on something that's of immediate concern. Planning is a wise thing, but it is preventive. Boards often respond to immediate pressure—neighbors rarely complain about an inadequate fire escape plan, they complain about cockroaches."

Initiating a Plan

It might be a bit of a mission, but getting emergency preparedness onto the agenda of your next board meeting is important. At the meeting, the board should be aware of the main types of emergencies an urban multi-family building should prepare for.

The possible disaster that's most on people's minds, by all accounts, is fire. The first question to ask in terms of a fire emergency plan is, "Are there alarm systems?" says James Long, a former New York City firefighter, who is now a press spokesman for the New York City Fire Department (FDNY). "Are there detection systems built in? Your building service people should be familiar with the system. In the event of a fire, there should be an immediate call to 911. From there, residents should try to help themselves in regard to extinguishers, which may be able to put out some smaller fires."

Yet another feared problem is a power failure, or blackout. Marolyn Davenport, senior vice president of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), says, "If your emergency lights are on battery backup, it's not always the case that this will work. You might very well want to keep flashlights or glow lights on hand."

A major flood in a building could also be cause for an evacuation. Many floods take place in the basement, but there is also the possibility of a roof tank flood, in which case an evacuation plan would have to be put into place. "When someone is doing something that will cause the roof tank to leak into apartments, when 15,000 gallons are coming through and destroy about 20 apartments, it's not a pretty sight," says James Hayden, president-elect of the Greater New York chapter of the Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM).

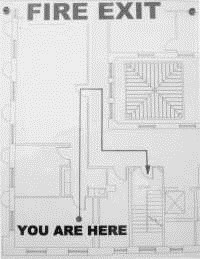

If there is an emergency—whether fire, smoke or flood—the American Red Cross in Greater New York has the same basic recommendations for all evacuations in all such situations. People should stay in their apartments if the problem is elsewhere in the building, according to the city Office of Emergency Management (OEM). But if a fire, smoke condition or other problem is in their apartment or if they're directed to leave, they should leave via the approved fire exits, whose location should be displayed on each floor—for example, ("In Case of Fire, Use Stairs A and B"). They should also be directed to close the doors behind them in these situations, so that if there's a fire, it won't spread further. Also, don't use the elevator.

One point to remember when creating an emergency plan is that management and staff can help people get out and give directions, but once the police and firefighters arrive, they're the ones in charge. And no one should re-enter the building unless the authorities give the OK.

The Red Cross also recommends that residents and their loved ones choose places to meet in the event of an emergency, plan what to do with their pets in the event of an emergency, and carry an emergency contact card with their name, names of family members and phone numbers. In addition, the organizaton recommends that residents turn off the water and electricity as they leave. The city's OEM recommends that even in disasters, residents lock their doors if possible, because you never know who might come in later on.

When creating an evacuation plan, be sure to include information about what residents should take in case they are evacuated, such as medical supplies, flashlights, batteries, first aid kits, a change of clothes, phone numbers, car keys and house keys.

Rare Emergencies

Boards and management teams spend very little time planning for extremely rare emergency situations, like bioterrorism, says Freeman. However, these issues do come up. Hayden believes condos and co-ops in "security-sensitive areas of the city," such as areas in Midtown or near high-profile locations such as the United Nations or Grand Central, need to be more aware of any suspicious activity going on around them, and should be tied into city-run hotlines.

"I think if you are located in those sensitive areas, your staff should get additional training—you might want to bring in a security consultant," he says. Once again, OEM gives several suggestions on how residents should be instructed to deal with serious security problems:

Your doorman and mail persons should be educated to be alert for suspicious letters and packages, such as those with a handwritten or poorly typed address and no return address, an unusual weight or lopsided appearance, or a powdery substance on the outside. If they or the residents themselves receive a suspicious package, they should be instructed to put it down, place it into an airtight container like a garbage can, and call 911.

And if, as terrible as it may seem, a resident receives a bomb threat, that resident, says OEM, should keep the caller on the line and ask as many questions as possible, listen for background noise, write down the conversation—and then call 911. Also, if an armed intruder enters the building, many authorities advise residents to leave the building if possible, and if that's not an option, to stay in your apartments and lock the door.

Getting the Word Out

Hayden believes that "your building staff is the key to your first line of defense. The superintendent, the doorman, the porter, whatever type of staff you have, they are the ones who are really going to maintain the building in a way that will keep people safe. They are the ones who should be directing everyone out of the building, and making sure that the Fire Department and police are called."

As far as the board is concerned, Freeman says that "[safety and security] needs to be an agenda item on the regular annual board meetings." Most people interviewed for this article, however, agreed that in most cases, it is unfair to delegate individual board members to be "fire marshals" or some such thing. Remember, the board members have jobs of their own. Rather, the management company and the superintendent—the people who are paid—are the ones who have to have responsibility, Freeman adds.

After a building consults with the experts, has had several meetings and now has an emergency plan, it's time to get the word out to the residents and staff.

A newsletter, flier or brochure is the most common way—preferably in large, clear print so that everyone can understand it. (If your building has many people who speak another language, such as Spanish, you should consider printing it in that language as well.) Information can include the location of the emergency backup lighting on each floor, where the fire alarms, stairways and fire extinguishers are, and other important details. Information can also be disseminated by phone trees and by email. And nowadays, many buildings, especially newer ones or large developments, have their own websites.

In a smaller building, one that might have only a part-time superintendent, it's difficult to have all the "bells and whistles" of a complicated emergency plan, explains Hayden, but you definitely should set email and phone contact lists. If there's no live-in super or maintenance staff, in that case it might be a good idea to designate a resident as a fire warden.

One final note—no matter what type of building you live in, you should make sure everything is kept up to code, for obvious reasons.

Helping the Infirm and Elderly

Emergencies in the building are particularly hard on one group of people, who might be called special-needs residents. These can include the elderly, people with chronic diseases, the disabled, even households with very young children.

One person who has more than two decades of dealing with the elderly and the infirm, and who has presented workshops at national and citywide conferences on the aging, is Judy Willig, executive director and founder of Heights and Hill Community Council, a Brooklyn Heights-based agency that addresses the concerns of the frail elderly. "When you're talking about evacuation, you need to be mindful of the things that seniors in particular need—what medications they'll have to bring with them. People talk about needing a `go bag,' but for older people, the go bag also needs to include a week's supply of medication," says Willig, who is also a co-op resident.

"In the event of an evacuation, you need to know who in the building will have trouble negotiating stairs," she continues.

In general, the super, staff or management company should have on file information about which people will need special attention in the event of an emergency. That way, when the Fire or Police departments arrive, they can be informed about who needs special attention.

No one wants to spend a lot of time thinking about the impact of fire, floods, blackouts or other emergencies on their building or development. But with a little time spent on the creation and distribution of an emergency plan, dozens and even hundreds of residents can spend even less time thinking about the worst- case scenarios.

Raanan Geberer is a freelance writer and editor living in New York City.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment