Home may be where the heart is, but these days, it’s also the source of enormous anxiety and concern for a great many co-op and condo owners. With the economy mired in recession and unemployment still hovering near the 10 percent mark, more homeowners than ever are falling behind on mortgage payments, maintenance fees and common charges. In turn, those situations are forcing many boards and managers into difficult decisions over how and whom to help within their co-op or condo communities.

The Scope of the Problem

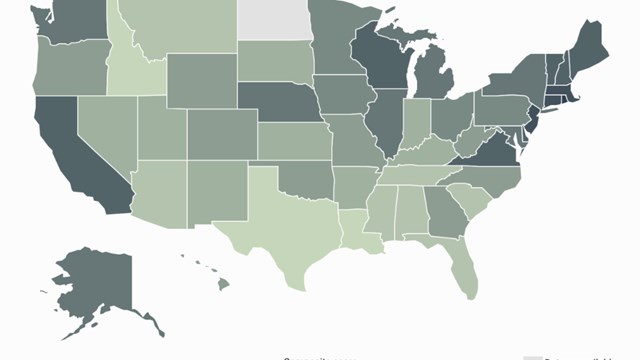

Compared to the housing market in other areas of the country—like Florida, California or Michigan, to name some of the hardest-hit—the slump in New York is certainly not as deep, but problems still exist, and have grown as the economy has worsened over the last year or so.

“These are some very, very difficult economic times that people are going through and it’s feeding its way down to the condo market,” says attorney Marc H. Schneider of the law firm Schneider Mitola LLP, who works with a lot of properties in the Long Island area. There, he says, he has seen a wide range of condo communities that are facing problems, from communities with a very small percentage of foreclosures all the way up to buildings with as much as 15 percent of their units in trouble.

In general, condo building communities are facing a far rougher situation than co-ops. According to attorney Andrew P. Brucker of Manhattan-based Schechter & Brucker PC, although more individual co-op shareholders are facing financial difficulties now than in the past, “In my opinion, there is not a great increase,” he says. The reason? “Co-op boards are very tough when it comes to financials. So whereas a bank might accept a [prospective buyer's] application, it’s very possible that a co-op board might reject them. We have seen this many times. Therefore, we believe that the co-op shareholder population is actually financially stronger and more secure than the average person in the general population. We believe that is why there has not been a major increase in arrears in co-ops.”

That's in contrast to condos, Brucker says. “We have seen a definite increase in arrears in condos,” he says. “The reason for this is simple. In the typical condo, the board does not have to give consent. Although the board asks for financials, they typically cannot reject [a buyer] based upon poor finances.”

Easing the Burden

For those individuals and families who do find themselves facing financial hardship, the prospect of losing their home is a terrifying worst-case scenario. While most unit owners and shareholders never get to the dire point of actual foreclosure, many may find themselves falling behind on common charges and fees, which can lead to bigger issues down the road. Today, most boards are recognizing the hardships that exist for folks who are out of work or facing other financial distresses, and are working hard to find ways to ease these burdens for their residents while still upholding their fiduciary duty to the larger building community.

As both an attorney and the long-time president of her 56-unit condo building on Manhattan's Upper East Side, Helene Hartig has seen all sides of the issue and feels that helping is not only something that neighbors should do for one another, but that ultimately may help prevent other problems before they start.

“I believe that cooperatives and condominiums are communities, and that it’s a board’s obligation to attempt to work with unit owners who may be experiencing catastrophic events, including deaths in the family, job loss, or health issues,” Hartig says. “Forcing an owner to struggle alone, or to sell at a below-market price ultimately helps no one and may even decrease property values in an already depressed economic landscape. It may also result in disruptive behavior in the unit owner, which can adversely impact the quality of life in the building.”

Property manager Steven Greenbaum of Mark Greenberg Real Estate Co. Inc., agrees. “These people are the board’s neighbors,” he says. “Nobody wins when this sort of thing goes to court. It won’t get you the late fees, it won’t get you the late payment. The general theory is that if someone comes to the board and says ‘I’m having a hard time paying but I’d like to make this payment plan’ —I’ve never had a board say no.”

The burden to make things work, however, cannot fall solely on the board or management. Unit owners and shareholders have to be forthright and upfront about their situations, rather than letting things spiral out of control.

“Boards are usually very amenable if a person comes to them in advance before the board has to start any legal action,” says Greenbaum, adding that if a person wants to suggest a possible payment plan in order to catch up on past due fees and charges, the board will usually listen. “And as long as they stay current and keep to their agreement,” Greenbaum says, “everything should be fine.”

According to the experts, any and all payment plans must be determined by the board—not the management. “Decisions in regard to allowances and so forth should be made by the board,” Brucker says. “The manager should make no deal without the board’s approval.”

And when it comes to making those agreements and allowances, the board must be careful to examine every situation on a case-by-case basis. “You can’t have a cookie cutter approach, but you can have a case-by-case approach,” says Margie Russell, executive director of the New York Association of Realty Managers (NYARM). “Just as you would when you’re doing approvals for new shareholders, you have to look at everyone individually.”

Boards, Brucker says, have “a tremendous amount of leeway in making deals.” This ability falls under the Business Judgment Rule, which says that a board can make decisions without interference or second-guessing by a court, provided the decisions are made in good faith and for a legitimate corporate purpose. This allows them to work with residents and try to find creative but fiscally responsible ways to solve these very difficult issues.

Residents looking for some of that leeway will have to prove their hardship as well. Russell underscores the reality that these types of situations require a thorough examination of the person’s situation. “It comes down to re-evaluating someone’s financial situation,” she says. “What kind of risk are they? There has to be a top-to-bottom review of that person’s credibility. It’s proper to look at the full picture of that person, their credibility in the past, their ability to secure employment. It has to be on a case-by-case basis.”

How Nice is Too Nice?

As much as board members might want to help their troubled neighbors, they have to remember that their first responsibility is to the condo or co-op as a whole. “Certainly, your fiduciary responsibility is primary,” Russell says. “The human relations side has to take a back seat. The board is not running a charity. For co-ops, it’s running a housing operation for the sake of their shareholders. They’re going to have to wear blinders sometimes.”

Greenbaum agrees. “We’ve had to say we’re going to be tough, because we do have to be tough,” he says. “I’ve seen collections become a big issue in many, many buildings. We’ve had to send out letters saying pay us versus paying your MasterCard bill. Go work it out with your credit card company.” Buildings, he says, especially smaller ones, often have to hold a harder line because otherwise, the whole community of residents could suffer. “Imagine if 10 percent of your building is behind on their payments—you won’t be able to pay the building’s bills.”

Situations also become very sticky when and if word gets out that the board has helped one person but then perhaps does not help another. “Obviously, any exceptions for shareholders and unit owners must be carefully considered,” Brucker says. “For example, if the shareholder is the brother-in-law of the president, or even an ex-director who served for decades, I would be very careful, since someone might claim this was not done in good faith.”

In co-ops and condos, though, everyone knows one another so there is always the chance that someone can claim bad faith. If, however, it’s apparent that the board made a good financial decision—or example, by lowering someone’s billed rent by $2,000 they’re able to get it paid immediately versus spending $10,000 to hire a lawyer – the obvious dollars and cents benefit will protect them.

When trying to find solutions for individual financial issues, it’s important for the board to not do anything that might become a burden for the other residents. For example, the board “shouldn’t waive a percentage of the common charges,” says Schneider. That’s because in most condos, the governing documents dictate that those missing charges then must be covered by the rest of the residents. That can lead to heated questions of “Why am I paying for the guy who’s not?” Those are the types of questions and potential disagreements boards want to avoid at all costs.

Hartig agrees. “Showing empathy for otherwise responsible shareholders in distress does not mean waiting indefinitely for payment – especially of base recurrent charges,” she says. “Nor should unit owners be forced to pick up the slack for their delinquent neighbors who lived beyond their means or elected to buy a Mercedes instead of paying maintenance or common charges.”

And sometimes, the board simply has to face the hard fact that it may be impossible to help. While it’s a very difficult reality for all involved to face, Brucker says, the sad truth is that “Sometimes people just cannot afford their homes, and they will have to move.” And that realization often just opens up a whole new set of difficult questions for the already strapped homeowners – how do they move? How do they sell their co-op or condo? These are the very difficult, very painful choices facing residents today.

Although there are signs that New York’s housing market is starting to improve, it’s unlikely that boards and residents have seen the end of financial hardships. By talking and being forthright, however, it should be possible to weather this economic storm together and one day soon, restore stability to the one place we all need it most: our homes.

Liz Lent is a freelance writer, teacher, and a frequent contributor toThe Cooperator.

Leave a Comment