Condos and co-ops are unique in their management structure, of which there are two levels: the board of the association or corporation, which governs the community on behalf of the unit owners or shareholders, and a hired management agent, who conducts the day-to-day affairs of the property. Of course, some communities go their own way and choose to self-manage, but they are the exception to the rule—particularly in communities larger than 20 units.

The question is, in professionally managed multifamily communities, how much responsibility and authority does a board delegate to outside management, and how does that affect how a given community functions?

The Spectrum

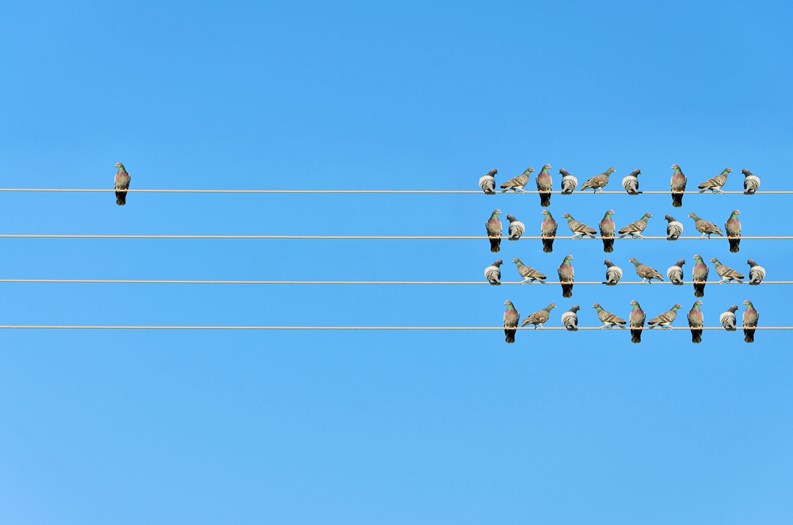

While each and every board is different and has its own style, managers report there is a ‘spectrum’ to board styles that ranges from minutely to barely involved. “There are two kinds of boards,” says Dan Wollman, CEO of management firm Gumley Haft. “They can be autocratic and dictatorial, or collaborative. In my experience, more are autocratic—and that has to do with the fact that most owners are ambivalent and apathetic. They don’t actually want to be on the board, which effectively leaves one or two active, engaged people on the board to run the building. This is very common. It’s simply the more pervasive style. Personally, I prefer a collaborative board, one that wants to be there. Collaboration allows for everyone to give an opinion and make a consensus decision, even if it’s not the one I personally recommend. I also like a ‘big-picture’ board—one that’s involved, but not bogged down with minutia. A board should never spend an hour discussing what type of cut flowers should be placed in the lobby. I want them to see where we are spending their money for a big project. It’s important that they see and feel where the money is spent. It gives them a far better perspective when they talk to shareholders—and that’s extremely valuable.”

Bryan Hughes, president for New England for FirstService Residential, says, “This can be difficult to generalize as each community, and each board, has a different flavor. They are made up of people, so each situation is different.” He divides his boards into three categories: too engaged, appropriately engaged, and disengaged.

“For management, disengaged boards may be easier to deal with on a day-to-day basis,” says Hughes, “but that isn’t necessarily a good thing. Although in those communities board micromanagement isn’t an issue, it’s often difficult to influence the board to make needful decisions. This demands extra time from the manager to educate and re-educate on circumstances and issues, and often manifests as deferred maintenance if the budget isn’t properly funded or the manager isn’t empowered to take care of the property.”

At the same time, a board that is too engaged can make management of the property difficult. “Part of the fiduciary responsibility for the board is to oversee management,” says Hughes, “but this doesn’t take away from the board’s primary duties to cast vision and to vote. If they’re too involved in the day-to-day, they lose the perspective that they need to have to focus on the greater macro-picture of the property.” Hughes concedes that board micromanagement is sometimes a reaction to previous experiences with poor management. But just as often, “boards are simply over-engaged thanks to members’ control issues, or as a result of politics within the board creating fear and anxiety.”

Hughes goes on to say that an appropriately engaged board is the best balance for the community and for management. “The board should be engaged beyond the monthly meetings,” he says, “but not so engaged that they burn out and can’t review things objectively. Perhaps some managers prefer the board not be involved, but we find it’s best when there is a true partnership.”

In terms of how board style affects his ability to effectively manage a client property, Wollman says, “When a board is busy with minutia, it’s hard to manage. If we’re discussing what kind of flowers to put in the lobby for an hour, we can’t get things done. We don’t need to discuss flowers for an hour—it’s not productive. The board should make that decision without me.”

Micromanaging from the board also short-circuits a building’s or association’s chain of command, Wollman adds. “Board members really shouldn’t involve themselves in managing the staff,” he says. “They should leave that to us. Say for instance that a doorman is inappropriately dressed. It’s the super’s job to speak to him. If a board member starts directly disciplining staff, they undermine management’s authority, which just makes it harder to run the building.”

Sometimes a building staff member with a complaint will find a sympathetic board member who will listen—which on its face might not seem problematic, but in reality “often creates conflict and mucks up the system,” says Wollman. “The board’s responsibility is to make policy and procedure; it’s the manager’s responsibility to carry it out. We institute it.”

Pros & Cons from Both Perspectives

As with a marriage, managers can’t go into a relationship with an elected board intending to change it; they have to be prepared and willing to meet the board where they are, and work with whatever dynamic presents itself.

According to Hughes, “Part of the role of the manager and management is to adapt. But by ‘adapt,’ I don’t mean that the management company or manager should change who they are—but rather that they recognize what attributes they will need to utilize most for this particular board and property. Some of this is skillset, and some of this is personality. In the end, management also needs to have the strength to recognize if it just isn’t a good fit. Sometimes management can just ride out an antagonistic board, but in an industry with an ever-shrinking pool of qualified managers, some of the toxicity levied by boards should cause management to consider whether a particular association relationship is doing more harm than good.”

“The truth,” adds Wollman, “is that with an autocratic board, I’m usually dealing with the president only. Lots of times, just dealing with one person makes it easier for me to manage the building in certain respects. From the perspective of the board, though, it can lead to second-guessing from others in the building if things don’t go well. People don’t care what’s happening and how it happens—when it works well. When things go awry, that changes. In truth, this type of board approach is poor governance, even if it generally works well on a practical level.”

Wollman suggests that a bigger problem is when people get on the board to pursue a personal agenda. That’s definitely not helpful, and can lead to problems in decision making and conflict with other board members and residents. Overall, he says, collaborative boards take longer to make decisions—which is not to suggest that it takes forever, but that issues are vetted more thoroughly, which is a good thing. “There are a lot of opinions in the room,” he says. “Sometimes a stronger party can control the group. It’s also more time consuming, but better for the building. Collaboration leads to less second-guessing, since it’s a group making decisions, and not just one person. If the board is truly democratic, it’s easier when board members see residents in the elevator and are confronted with a question.”

Board Evolution

Can a board’s culture and governance style change over time? The answer is yes, and that stylistic change can be the result of several different factors. Most likely, the change is a result of new board members with differing views on management style joining the board and influencing how it operates. Another possibility is that existing board members themselves evolve over time, learning from their mistakes and perhaps becoming more comfortable in their positions.

“Turnover is certainly the most common driver for stylistic changes,” says Hughes. “This can be accelerated if these changes come on the heels of individuals who got on the board to ‘fix’ something that the community perceived as being wrong. Of course, hopefully the manager is coaching, listening, and engaging the board on how to mitigate these risks, but they may happen regardless. If so, there is some technique in how the manager can help a potentially antagonistic individual get up to speed on new and previously confidential information that may have driven unpopular decisions by the old board. Certainly, helping them have a voice can reduce the risk of contention and help them save face.”

Wollman concurs; style evolves over time through fundamental changes on the board, people coming and going, and new leadership. “I have a client who is the board president of one building. He has strong views and can control the board, convincing its members that he has better ideas. Style and views will alter dynamics in a building sometimes. Views on money will alter style as well. Say the building needs a new roof. Some on the board may not want to spend the money, and would prefer to get a longer life from the existing roof by doing repair work. Some others may think board service is a popularity contest. That’s a problem. Board service and management are a responsibility to the community.”

Regardless of style, both managers and board members have to keep one important goal in mind: the long-term success of the property. That requires a symbiotic relationship between the board and management. The nature of that symbiosis can look a lot of different ways—as long as it produces the desired results.

Cooper Smith is a staff writer for CooperatorNews.

Comments

Leave a Comment