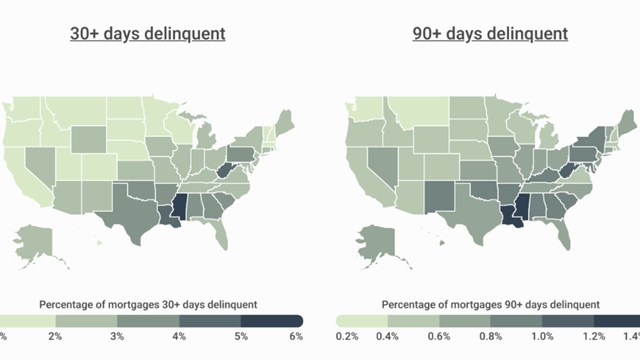

A primary rule of cooperative living is that everyone pitches in their fair share. This applies to monthly maintenance payments, special assessments, and any other monetary obligation that allows the association to maintain quality of life for the residents and their collective property. It follows that, should someone be unable or unwilling to pony up for their piece of the proverbial pie, ramifications will be felt from the board on outward. It's to the benefit of all parties involved to sort these situations out as soon as possible, as eviction proceedings – the worst-case-scenario, usually – can be painful and drawn out, leading to dangerously depleted reserves and serious morale problems among the remaining shareholders, forced to carry the weight of the delinquent.

Baby Steps

It behooves a board to act rationally if a shareholder is in arrears; should someone fall a month behind, that is not necessarily reason to ring the alarm. But it is incumbent that a board stay aware of everyone's payment situation, such that it can act when the time comes.

“We look at our monthly sheets,” says Burt Wallack of New York-based Wallack Management. “If someone is a month in arrears, we normally send out a reminder, at which point, I'd probably say that nine out of 10 people just pay. If you have someone two months in arrears after we send out that first notice, we'll send a legal letter saying that they must pay. Finally, if they don't pay by the end of the second month or the beginning of the third, then we go to legal.”

In many cases, a little nurturing and sensitivity can go along way toward sorting out a sensitive situation. “In many cases, a shareholder is sick, or they've lost their job, or something similar is going on, and I would say that most boards have a level of patience in letting people work things out, whether that means getting their lives together or selling their apartments,” says Eliot H. Zuckerman, a partner with the law firm Smith, Gambrell & Russell, LLP, in Manhattan. “If the board thinks that there's no realistic hope that a shareholder will be able to get themselves back together financially, however, that person will have to sell their apartment, as the board can't let the shareholder continue indefinitely without paying, for the obvious reasons.”

Wallack concurs. “If I have a shareholder in truly dire financial straits,,” he says, “with work and their business, or personally, say with a divorce, I will speak to them and attempt to work out a payment schedule. And that probably works about 90 percent of the time as well. Even when we do have to go legal, via which their families will by necessity become involved, I will speak to them and try to ascertain when they'll be able to pay.”

Size Matters

When a shareholder does fall behind on their payments, the ramifications within the community at large depends on the size of that community. The smaller and more tight-knit the association, the faster word tends to travel.

“In larger buildings, [a shareholder going into arrears] has much less of an impact on everyone else,” says Zuckerman. “In most cases, boards will keep things relatively confidential such that no one sees or feels it – at least in the beginning. But, at some point, if it's clear that the shareholder is not paying and is not going to pay, then the board will start an action, and courts tend not to be sympathetic.

“Now, I haven't heard of a situation wherein someone actually cold-cocked somebody else in these scenarios,” he continues, “but the smaller the building, the greater the impact and the greater the animosity. Because in a lot of these smaller buildings, someone having to pay even a few extra dollars can be a real strain. And they may have to pay for lawyers as well. People who know that they cannot keep up with their payments usually sell their units, but it's the contrarians who just want to fight, and either don't care enough about the impact it will have on their neighbors, or will even relish the chance to hurt their neighbors, that become real problems.”

And while smaller associations may be well aware of other shareholders' affairs, it's in the board's best interests to keep everything as intimate as possible. “Payments are board business,” says Steve Birbach, president and CEO of Vanderbilt Property Management LLC, in Glenwood Landing, New York. “Boards shouldn't discuss them with outside shareholders, and the information shouldn't leak out into the community. Generally shareholders won't know if a few people aren't paying maintenance in a typical building, and a board by rights shouldn't be telling anyone if that's what's happening. That said, if you're a board member, and the guy in 2G isn't paying his due, and you have an assessment to make up for whatever is missing in the budget, you're going to be mad and annoyed.”

The Bottom Line

It falls to the board when all is said and done to act in the

interests of the cooperative, which may well be at odds with those of

a particular owner, even if that owner finds themselves unable to pay

fees for truly sympathetic reasons. That said, should there be a

lender involved, boards have another approach toward recouping their

money outside of forcing someone out of the building.

“The

first thing that management should do is to check the files or run a

title search and notify a lender, should one be present,” says

Birbach. "There's something called a recognition agreement in a co-op

that obligates the lender to make maintenance payments on behalf of a

shareholder. They don't always do this, but it's definitely a first

step toward making someone current."

“At the end of the day, this is a business,” Birbach concludes. “We have to manage the co-op as best as we can, and this is how we're going to do it. We have to protect the rest of the unit owners, and we have to get paid. So either you pay us, or we'll auction off a unit and get paid that way.”

Mike Odenthal is a staff writer at The Cooperator.

Comments

Leave a Comment