By and large, a board and management company can expect payment from residents for monthly fees to be received on time and in full. These all-important funds keep day-to-day operations moving forward without delay. There are situations, however, that arise which can offset the balance sheet. Circumstances run the gamut but in the end, monies that can’t be collected end up costing a whole lot more than the losses they represent.

“The most common excuse given is that the person simply can’t afford to make the payment whether it is true or not,” says attorney Ronald Steinvurzel, a principal of the White Plains-based Steinvurzel Law Group, P.C. “These people will ask for patience and will offer the excuse du jour which most recently has been the economy.”

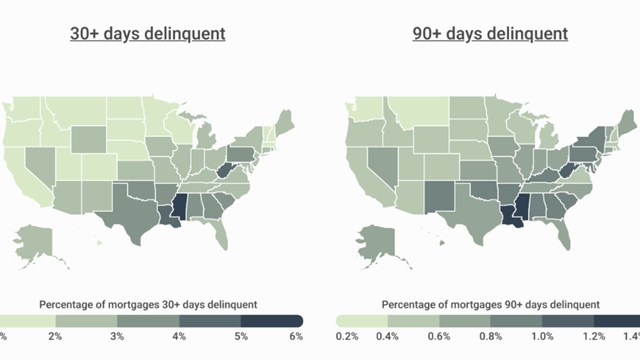

It is true that the economy has played a major role in not only late payments but the ability for some people to make their payments at all. This is due, in part, to high jobless rates. For example, according to the New York State Labor Department, the Big Apple’s unemployment rate increased to 9 percent in December, compared to a national rate which dropped to 8.5 percent.

“In many cases, boards and management companies hear excuses that the resident is owed money or lost their job, as of late the economy is the excuse, and what a great excuse because everyone knows it to be true but that does make the situation any better,” says Steinvurzel.

The way in which a board determines how to handle collecting monies that are past due is always different as respective bylaws dictate the course of action. In most situations there is a grace period between five and 15 days after the payment is due which is usually the first of the month. “If it is deemed a temporary issue, then it is simply a matter of collecting the money,” says Michael A. Esposito, a certified public accountant at Kleiman & Weinshank, LLP. “If it’s a chronic use, you have to then factor the losses into your budgeting.”

To this end, most boards will assume that there will be a percentage, albeit small, of delinquencies which impact the rest of the community. This is considered an unfair charge to residents that faithfully pay their fees. “If, for example, you were trying to collect one million dollars, you have to figure that you will not collect that amount and will collect something less,” says Esposito. “Theoretically, you’re still going to have to come up with that million dollars so common charges for all residents have to be raised to say 1.1 million dollars. This is the downside of living cooperatively.”

Mediation Before Litigation

While most boards have an attorney on retainer, they depend on their management company to keep them apprised of any delinquencies. This communication chain of command can add more time to the situation. For example, if a resident misses a payment, the management company will normally not send a notice to that resident until the grace period is over, and in some cases will wait weeks longer. The management company will inform the board at the next monthly meeting. So before any action can be considered, and providing the resident didn’t make good on the first missed payment, the delinquent resident will likely have missed two payments before any serious action is taken.

“Common problems are people losing their jobs or claiming bankruptcy and the management company are the ones that have to be aware of the reason that payments are not being made,” says Albert M. Kushnirov, CPA and president of Greenberg & Brennan, CPAs, P.C. In Kushnirov’s experience, “the collections process is a very long road.” Depending on the board, the rules for collection of delinquent fees are usually covered in the bylaws or “house rules,” the propriety lease, the offering plan, or management policy. Boards generally prefer that if a written notice doesn’t spur activity to have the management company call the resident directly. “Typically, this type of follow up will continue for a month or two.

Eventually, if these steps don’t yield a response, an attorney will be contacted to draft a similar letter with the threat of legal action citing relevant provisions of obligations in the controlling documents,” says Steinvurzel.

While banks and lending institutions penalize a person for being late on a car loan payment or credit card payment with a late charge, boards often do not. Their main goal is trying to recoup monies lost and up and until legal counsel is brought into the picture, they look to remedy the situation with as little cost as possible.

“Boards do not have a lot of extra money and they do not want to spend money on attorney unless they have to,” says Steinvurzel. “If a resident is $1,500 or $3,000 behind, boards are not going to be so inclined to spend hundreds of dollars on a lawyer to try and collect it. It is more likely they will wait until that tenant or condo owner become so delinquent—several months—that the amount of money in controversy is more relevant for purposes of a legal dispute.”

Suspending Privileges

Charging late fees, filing liens and starting foreclosures is the most common avenue and method to persuade members to pay; however, many associations also have the ability to suspend privileges to any member in arrears. The theory being that the assessments pay for those privileges and if a member is not contributing to the cost of those privileges and/or amenities, then they can be deprived of the benefit of using them.

Some states, like Florida, for instance, have provisions codified into law allowing homeowner associations to suspend common area privileges. And in New Jersey, a 2011 court decision allowed a condo board to suspend the parking privileges of an owner in arrears.

According to attorney Jeffrey S. Reich, a partner at the Manhattan law firm of Wolf Haldenstein Adler Freeman & Herz LLP, it’s a trend he is seeing happening more frequently among New York’s co-ops and condos.

Many New York buildings that were built in the 1950s or 1960s and converted to co-op lacked the top-flight amenities we see in many newly-constructed buildings today, he says.

“They didn’t use to have a lot of amenity spaces. They didn’t come with gyms and children’s playrooms and business centers and theaters. So probably in 1988 or 1991 when you were going to collect funds, cutting off an amenity wasn’t much of a threat. But today, we see all of these buildings that come to market with all of these great amenity spaces, and therefore, it opens up and makes it a more meaningful penalty to say you can’t use them,” says Reich.

With technology today it’s also much easier to restrict access, he says. In 1980, for example, you didn’t have a key fob system or an access card that let members into amenity spaces, you probably had a regular key. You could send a letter to a co-op shareholder or a condo unit owner and say you can’t use the space. But what building had the staff around to enforce it, he adds.

But a key fob system or access card can be programmed to cut off access to a particular person who is behind on their payments. “It’s more meaningful. It’s become more easy to effectuate which people access these spaces. And I think another element that made this really part of a growing trend is the fact that many buildings that come online today are condos instead of co-ops.”

When you had an arrears situation in a co-op, at a minimum, the building’s lien came in front of the bank. So even if you couldn’t collect today, you’d eventually get your money by going through the normal legal process. “Ultimately the co-op was in a really good position. At the end of the day, they were going to collect their money,” exclaims Reich. Thus, it wasn’t as important to find these other alternative methods of collection.

“But with a condo board, because its lien comes behind the lender, and we saw what happened to the economy over last couple of years where units lost value and there was no equity in the unit, so a building had no chance in collecting its arrears. So condominiums had to get very creative to find ways to collect.”

“I’m seeing it more in condos than in co-ops,” Reich adds, “and in co-ops they tend to have been older properties so they don’t largely have the same amenity space issues. I have seen in a number of condos, including some I represent, where there’re actual bylaw amendments being proposed and being passed, which make this the law of the building—where your rights will be cut off.”

He cites the case of a six-story building in Soho where the condo board cut off elevator access to residents in arrears. “It wasn’t illegal to do and they were able to program out that elevator so it didn’t go to that floor-thru apartment where that shareholder was in arrears. There are different things you could put in the bylaws where you don’t allow use of the amenities. They talk about taking your name off the directory, not allowing the doorman to call up guests or packages. There is definitely a growing trend,” says Reich.

A Special Assessment?

Anytime a board experiences a shortfall of fund, they might be forced to conduct a special assessment to make ends meet, especially in this economic climate, explains Kushnirov. “During debt collection proceedings, a few times we have seen condominiums activate a special assessment to make up for the monies lost.” While this decision is made usually in conference with the management company, Kushnirov said he offers support in the event they are “ready to move forward.”

Ultimately, the old adage of a few bad apples upsetting the apple cart is realized. Residents are not without recourse in that they can request information from the board as to who is not making payments. They are not allowed to harass the delinquent party by due to governing laws; they are entitled to know why a special assessment was executed and why their monthly dues increased.

Fair Collections

If legal action is taken, it can take months if not over a year for the case to be settled. The nation’s consumer protection agency, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), is the entity that enforces the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA). This prohibits debt collectors from using abusive, unfair, or deceptive practices to collect from a delinquent party. Under the FDCPA, a debt collector is defined as a person who regularly collects debts owed to others and includes collection agencies, lawyers who collect debts on a regular basis, and companies that buy delinquent debts and then try to collect them, notes the FTA. “What this has done is codified moral and ethical means of the collection of debts,” says Steinvurzel. “This has created a heightened awareness for collections and this applies for condo owners in the New York metro area, too.”

In many cases, the location of the building and the demographics that comprise the residents make a difference on the frequency of payment arrears or the juxtaposed value in the event collections occur. “We deal with a lot of high-end buildings so there is a lot of equity in these apartments. If you go to the outer boroughs or suburbs where people have eighty to ninety percent mortgages, there is no money in that apartment or property,” says Esposito.

Since condominiums owners and co-ops owners have a different ownership structure, in many cases, Kushnirov explains that the former will continue to pay their mortgage payments but lapse on their monthly fees. “To avoid getting in trouble with the bank, condo owners will continue to pay them but not their monthly fees. This happens on a regular basis,” he says.

“A co-op owner,” Steinvurzel adds, “is really just a lessee with ownership of shares in a corporation. The board can initiative an eviction proceeding. It is a landlord/tenant relationship. This can easily take three to six months,” he continues. “With condominium owners, it becomes an issue of foreclosure on that unit by the board. This proceeding is far more time costly and time consuming with a six to 18 month window depending on the site, the judge and the parties involved.”

W.B. King is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment