A conflict appears to be brewing between a local preservation group and New York City’s Department of Buildings over an Upper East Side condo tower project that the latter approved.

According to a piece last December in Crain's New York Business, the tower at 249 East 62nd Street would incorporate a “mechanical void” to raise some of the condo units such that they would offer better views and thus sell at higher prices.

Crain's describes the project as such:

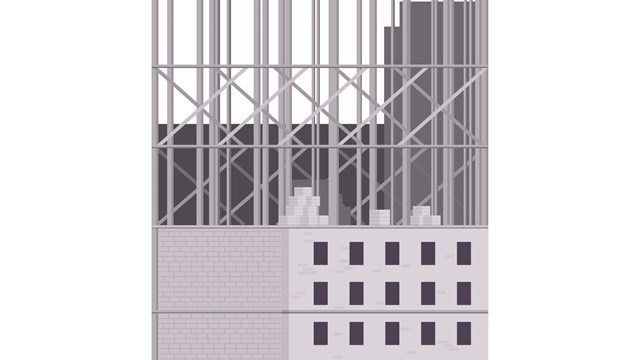

“The base of the building seems fairly traditional, with about 15 stories worth of apartments rising from the sidewalk. Atop those units, however, is a mostly hollow pedestal stretching another 150 feet into the air. It contains a few floors of mechanical space with extraordinarily high ceilings, along with some amenity space. Most importantly, it is largely exempt from rules governing how much can be built on a particular plot of land, allowing the height of the overall tower to rise without being penalized with the loss of much square footage. Beginning at around 300 feet up, another 12 floors of apartments are proposed to be stacked on top of the so-called mechanical void.”

Both the preservation group, The Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts, and planning consultant George Janes filed objections to the project last November. They disagreed with the math used in determining the project's size and layout. The opponents also asked why the DOB would approve a building that utilizes one of these large mechanical voids at all. (Developer Real Estate Inverlad did not offer a comment to Crain’s about this project).

In similar cases thus far, the DOB reportedly has tended to side with the developers. But whose interests do these voids serve? Is the DOB correct? Do the preservation groups that levy complaints lean too conservative? Or are developers exploiting existing loopholes and throwing money at problems in a way that is detrimental to historic neighborhoods?

Money Talks

By definition, a “mostly hollow pedestal,” as the mechanical void is described in Crain's, cannot offer much functionally to a residential property. So what is its relevance in this particular project?

“While I don't do development, and as such this is outside my professional world...as a citizen? This seems like a clear example of a developer ignoring the spirit of the rules for economic benefit,” opines Rick Lefever, President of Facade MD Architecture and Engineering in New York City.

Barry Weinberg, a member of the Housing, Zoning and Land Use Committee for Community Board 9, which serves Morningside Heights, Manhattanville, and Hamilton Heights, says: “It seems evident to me that developers are taking advantage of what was meant to be a common-sense acknowledgment that sometimes building mechanical systems need to be placed on roofs, which shouldn't count against the total residential or commercial density limit, and are now structuring their buildings around this loophole in crazy ways, to the detriment of communities around their sites. While misuse of the mechanical exemption isn't exactly new, developers, realizing the DOB's laxity on the issue, are now pushing it far beyond the practical allowance with which it was intended.”

“As for community groups' responses,” he continues, “I think that many people rightly feel that, in our current era of extreme inequality, weakened rent stabilization, and crumbling infrastructure, it does not make sense to stuff further overpriced condos into Manhattan that result in the surrounding community experiencing tenant harassment and displacement, overburdened school and transit infrastructure, and the blocking of light and air.”

The case appears to be another example of the long-standing battle between developers of high-end luxury residential housing and those who want to preserve neighborhood aesthetics. As long as people are willing to pay for exquisite views, developers will most likely find ways to provide them, even if that means testing current zoning ordinances. Meanwhile, community organizations will probably have to keep fighting, whether that means on a project-by-project basis, or to establish stricter height regulations in their neighborhoods.

Mike Odenthal is a staff writer at The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment