The mortgage crisis has been felt throughout the country, and markets and individuals alike have moved from denial and bargaining to acceptance of the recession and its attendant challenges. And while New York City’s co-op and condo market has not been affected in the same way as many other areas of the country, it is most definitely experiencing the effects of a deeply-troubled economy.

Early Signs of Trouble

Although different areas of the U.S. started feeling the pinch at different times, there were some indications of the economic problems to come before the scope of the situation became better understood.

“You started to see it a year ago in July,” says Melissa Cohn, president of Manhattan Mortgage. “Banks that all of a sudden saw huge default rates on mortgages began tightening their guidelines, started requiring better credit and lower ratios for qualifying and going back to business the old-fashioned way. The greatest impact in New York City is really the loss of no income verification for self-employed people. There are a lot of self employed people in the New York area.”

And while there were rumblings of trouble back then, most people didn’t take them seriously until September 2008, when the city got a wake-up call of sorts.

“The whole market started to get the jitters back in September,” says Patrick Niland of First Funding of New York LLC in East Rochester. “There were people talking about it before then, but I would suspect that no one was terribly disturbed by it until September. Bear Stearns started it. That was really the trigger, because that was a major Wall Street firm. Up until then people knew about problems and talked about them, but Bear Stearns got hooked and people said, ‘This is a little wider than we thought.’ From there it kept getting wider and wider.”

Mortgage Problems in New York

While subprime lending was a huge problem throughout the country, it was less of a problem in New York’s co-op and condo market, primarily because the sky-high prices in Manhattan and its surrounding neighborhoods acted as a filter to all but the wealthiest buyers—not the demographic looking for (or being offered) subprime mortgage deals.

“There was very little subprime lending in the New York marketplace,” says Melissa Green, a licensed real estate broker with a commercial lending background currently affiliated with Ed Tristram Associates, and a board member of her own co-op.

In addition, the number of late payments and defaults is also less in the city.

“There are people who are late in the New York area, but that is much smaller percentage than anyone in the country,” says Cohn. “We have the benefit of being in a jumbo marketplace, and subprime loans really weren’t available. The city is primarily an owner-occupied area and there weren’t a lot of investors. Manhattan has been the best performing area in the New York marketplace. Default rates are higher in the boroughs where the average apartment price was lower.”

Certain property types have also been affected more than others.

“In working-class neighborhoods, the people who got loans for one- to four-family homes are the ones that are affected,” says Green. “If an owner is living in one unit [and renting the others as income properties], what happens to the three other units when the landlord defaults and abandons the building? This crisis was being felt and worried about in the lower end of the housing market for a few years.”

And while subprime lending was rampant in many areas of the country, Green feels that subprime loans weren’t necessarily the main culprit in New York City’s mortgage problems.

“I don’t think [subprime lending] was so much a problem as overvaluation of the properties,” she says. “There’s a difference between that and giving borrower more money than they can handle on an adjustable basis. I think it was more an issue of the banks overvaluing the value of apartments.”

Another problem is the rising level of unemployment—particularly among people in the financial and banking industries. Job losses as well as little or no bonuses have impacted the ability of many people to handle their mortgage payments.

“I don’t believe that there’s been a huge drop in value the way you’ve seen in other areas,” says Green. “Our problem is unemployment. The people who took these loans may find themselves out of work. A lot of people who worked in the financial services sector expected to pay down their mortgages with their bonuses. I think we’ll start to see more defaults as Wall Street and the banking industry lay off more people. People who really thought they had secure positions may not be in the position they thought.”

A Sign of the Times

So how have things changed in the New York market? For one, banks have become more stringent in their requirements for granting loans and mortgages.

“Banks have tightened their guidelines, and now require bigger down payments and verification of sufficient income,” says Cohn. “They’re requiring more money in reserve after closing and you have to have good credit. Some banks now require a minimum credit score of 700.”

Lenders are generally looking at all the same information they would have a year ago, but these days they are paying a greater deal of attention to that information and asking more questions about it.

“Before last September 2008, if a co-op had 10 percent of units that were delinquent, a bank might not have questioned that,” says Niland. “Now, there will be questions as to why. Everyone is being more careful about analysis of the same information.”

The professionals point out that there is an upside to banks tightening their requirements, however.

“The fact that banks are being tougher on approvals will also ensure that we have a stable marketplace,” says Cohn. “We don’t have a wave of foreclosures, and that has kept values in better shape here than in other areas of the country. But prices have softened as the economy has weakened.”

Even though co-ops are typically low loan-to-value propositions, with the loan equaling less than 25 percent of the value of the property, co-ops are still vulnerable to other variable expenses fluctuating.

“For this reason, lenders are scrutinizing co-op loan applications much more intensely,” says Steven Geller of Meridian Capital Group in Manhattan. “To the point where they often require copies of the co-op board meeting minutes, to see if the co-op is working collectively and ‘cooperatively’ in maintaining the property. In this market, you only have one shot at the best lenders, you have to make sure to give yourself the best opportunity to take advantage of the low rates while they are available.”

The Effect on Co-ops

So how are co-ops themselves faring in the altered economy?

“There hasn’t been a significant negative impact on co-op foreclosures,” says Geller. “If a unit owner is foreclosed upon, the co-op takes back the unit, and only has to rent it at the price of the maintenance on that unit to break even. If and when this happens, the co-op is actually in a stronger position, able to subsequently sell the unit and hold the profit in the co-op’s reserve.”

In order for an entire co-op to fail outright, a significant percentage—30 to 40 percent, say—of its shareholders would have to default. However, that percentage could be lower or higher depending on the co-op in question.

“If 25 percent of the shareholders in a modest co-op in Queens stop paying their maintenance, that co-op would be in trouble because the other shareholders could not pick up the slack,” says Niland. “It would be different in Midtown Manhattan, where it could be as high as 40 percent and the co-op could still cover the fees, foreclose on the units and rent them out or sell them when market turns around. That’s why underlying mortgages are such a low risk. You have diversity in income sources.”

“It’s much harder for a co-op building go into default,” agrees Mindy Goldstein, senior vice president of National Cooperative Bank (NCB), a Manhattan-based lender specializing in co-op and condo financing. “If you have 100 units with two people defaulting, it’s not that impactful to the entire building.”

Goldstein goes on to say that not every lender has seen their world turned on its ear and its business stalled or stagnated. “I don’t think as lenders we’ve changed our criteria that much—we look at the same things we’ve always looked at; financials, budgets, things like that. That hasn’t really changed that much, and we’re still doing loans. We’ve always looked at financials and analyses. It’s not harder to get underlying mortgages—we’re still doing them. I think it’s affected other things like multifamily rental buildings, but our main business has always been co-op lending, and it continues to be.”

Buildings that would likely have had problems getting credit back in the boom times will likely have the same problems now, says Goldstein. “If something jumps out— like large recievables, for example—you ask questions, or if you see litigation, you do your due diligence and ask more questions. If you see large deficits, you ask questions. We’re always prudent in terms of our reviews and analysis, and you just have to consistently and continuously look at the information. We have to make sure the buildings we lend to are solid buildings—that’s always been our cornerstone. By performing our due diligence, getting the reports, getting the appraisals, the environmentals, the engineering reports, looking at sponsor-vs.-shareholder to ascertain what the differential is. It’s a matter of being prudent.”

Goldstein allows that her bank has pulled back on some of its unsecured lending, though she says that was never a large portion of NCB’s business.

“If a co-op needed a line of credit and didn’t have a mortgage with us, in the past we might have done that,” she says, “but we’re only doing that now on a very limited basis. That’s really the biggest change.”

As for more day-to-day business, even in the recession, “Buildings have Local Law work,” says Goldstein, “so we’re still giving co-ops refis and working with their underlying mortgages because they still need to keep their buildings up to code so things continue to run smoothly. It’s not just the financial component, but the upkeep as well. Co-op boards have to do what they have to do—I don’t see buildings spending money to do luxury-type projects and things. They’re doing Local Law work, maybe renovating a lobby if they’ve already started a project like that. It’s a whole picture—finance, upkeep, and so forth.”

No Immunity

That’s not to say that co-ops are immune to the turbulent times. The softening of the rental market—which, while slight so far, will likely deepen—could also become an issue for many shareholders and co-ops. With an increasing rental inventory, renting out a vacant unit might prove more difficult than it once was.

“Now there’s a ton of non-stabilized, market-rate units on the market,” says Green, “so even if you’re willing to give up your apartment, you may not be able to get a tenant who can cover your costs. As sale prices go down, subletting becomes difficult and we may start to see defaults on underlying mortgages when people start to not pay maintenance.”

And although underlying co-op mortgages are still a very low risk, some banks are no longer doing them.

“That’s become an issue,” says Green. “Smaller banks are still doing underlying mortgages, but I know WaMu/JP Chase is not. It becomes a financial issue because co-ops are not fitting into a lot of bank programs, and I think it’s going to be hard for them to find banks to deal with in terms of underlying mortgages.”

Additionally, because of the difficulty in getting a loan or refinancing underlying mortgages, building improvements or repairs might be put on the back burner.

“In co-ops, improvements will be affected, as well as anything that would normally require an additional mortgage or a shareholder assessment,” says Green. “It will be hard to assess people who are struggling economically in the first place, and you will start to see some deferred maintenance projects.”

“The banks that are still competitive in the underlying co-op lending market have layers of additional underwriting and due-diligence requirements, reflecting the added risk inherent in all commercial lending today,” adds Geller. “Condos don’t have the same need for underlying financing because unit owners are more directly responsible for their own capital needs. However, there are still projects that condos need to undertake.”

An Affordable New York?

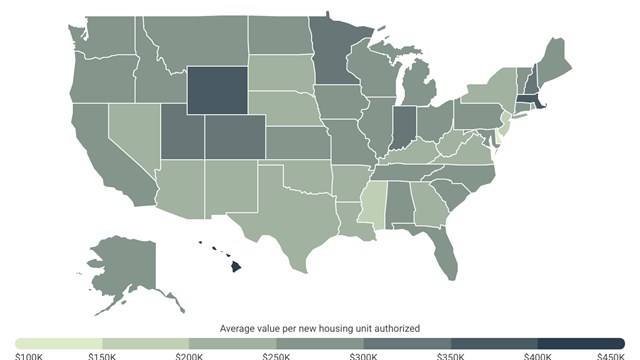

New York City’s real estate market has long been synonymous with high prices. So even with the drop in prices, “affordable” is still a relative term. Compared to other parts of the country—and even the state—the five boroughs still might not seem like a bargain to some. To others, a decrease in prices could put once unaffordable homes within reach. It could also force others out of the city completely.

“This is speculation,” says Geller, “but during past downturns, when rental and housing costs have not fallen with the economy, it has led companies out of Manhattan, looking for lower commercial and housing rents in the surrounding areas. This will be a function of supply and demand. Prices will remain high as long as there are people willing to pay those prices. With the layoffs on Wall Street, a large pool of prospective affluent buyers has all but vanished. Time will tell.”

With fewer buyers for existing construction, new residential construction is virtually at a standstill as well.

“In a recession, the biggest thing that would happen is that real estate values will come down and will continue to come down,” says Cohn. “New construction has basically come to a halt. Smaller developers are having trouble getting construction financing — and the commercial mortgage market is in much worse shape than the residential.”

“But as prices come down, the city becomes more affordable,” Cohn continues. “New York City became unaffordable to many people, and with values now down 10 to 15 percent it may become more affordable.”

However, affordability is subjective, and depends on the market and the buyer.

“The prices will come down to the market people are willing to pay,” says Geller. “Because it will always be prime real estate, because of its proximity to the financial, corporate, educational and recreational centers of the city, and will always contain luxury housing amenities, New York City will probably never be what someone from the Midwest would ever consider affordable. It’s not meant to be. It’s meant to be what it is, the center of the financial, corporate, arts and entertainment universe.”

Stephanie Maninno is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment