Property managers know that whether they're running a small, contained walk-up building, a multi-unit high rise, or a sprawling condo development in the suburbs, materials, capital and personnel all fall under their administrative jurisdiction.

Many of the jobs handled by property managers can be described in well-defined terms—send out monthly bills, attend meetings, file paperwork—but regardless of the size of the project, human resources are typically considered the most important and involved piece in any management puzzle. Managing human resources is both an art and a science, and requires a very specific skill set, particularly since peoples' homes and personal assets are involved.

Even a great manager may not be an expert in the management of human beings, but nevertheless, depending on the size and nature of a community, a manager might have to coordinate operations with a single superintendent or work with any number of doormen, porters, custodians and handypersons. Well-trained, motivated employees enhance the appeal and ambiance of any property adding to both the real and perceived value, but just as managers aren't necessarily born human resource specialists, great workers don’t just show up that way by magic their first day on the job. Good managers will avail themselves of the resources available to maintain and improve their own human-management skills as they build a viable support staff.

Who’s in Charge?

'Workforce,' 'staff,' 'human capital'—no matter what name is given to the people who service and maintain an association, it all comes down to “people power. According to Dan Wurtzel, president at FirstService Residential in Manhattan, staff management requires that a manager come to the task with a few fundamental tools.

“Whether a new property or an existing one, the tools are the same, a detailed job description, schedules, and training must be in place,” Wurtzel explains. “Make sure the job descriptions and the schedules are in sync and customized for the building. Every building is different, with different amenities and different nuances. Templates don’t always work.”

In addition, Wurtzel believes that all staff members, regardless of their job descriptions, need either to have customer-service skills when hired, or be taught them on the job. “Customer service is part of every job,” he says, and uses as example a floor polisher who, even though his job is limited to just polishing the floor, doesn’t keep mindlessly polishing when he is approached by residents or other staff members. “Ideally, he stops the machine and gives full attention to the person approaching him,” says Wurtzel.

Wurtzel has confidence that thorough, focused job descriptions lead to hiring the right people for each job; people who come in with the right background and skill set to perform the assigned duties. Careful scheduling results in minimal disruptions and in conjunction with good training, results in improved efficiency. Wurtzel believes in training for both managers and staff members. FirstService Residential has its own courses but he also encourages bringing in experts or specialists to teach specifics. Oftentimes a vendor can demonstrate a product or piece of equipment and take the guesswork out of the equation for staff members who will be using it day-to-day.

Knowing how to do their jobs well, and having clearly defined tasks has a positive effect on staff morale, as does supervisors' acknowledgment of a job well done. If a lack of motivation is noted, Wurtzel stresses the importance of understanding why there is a problem and where the breakdown has occurred. “Find the problem and fix it,” he says. “Patterns have a way of repeating, so don’t just use a Band-aid.”

If Things Go Wrong

Sometimes, staff management issues cause an association to lose its edge. As an example, Wurtzel mentions a particular building he encountered where daily upkeep had deteriorated. The physical plant was not quite as well-maintained and tidy as it should have been, and the staff was just 'okay,' rather than exceptional. Because the issues were widespread and somewhat non-specific, it was difficult to get to the root of the problem. Turns out, the property manager—who was the direct supervisor to the staff—was leaving early most days, and passing off his responsibilities to building staff, while failing to address issues of importance to staff members. The manager was counseled by his own supervisors but ultimately he was unable (or unwilling) to correct his behavior, and he left the position. With a new resident manager in place, Wurtzel says the staff’s morale recovered, and the property was restored to its former excellence.

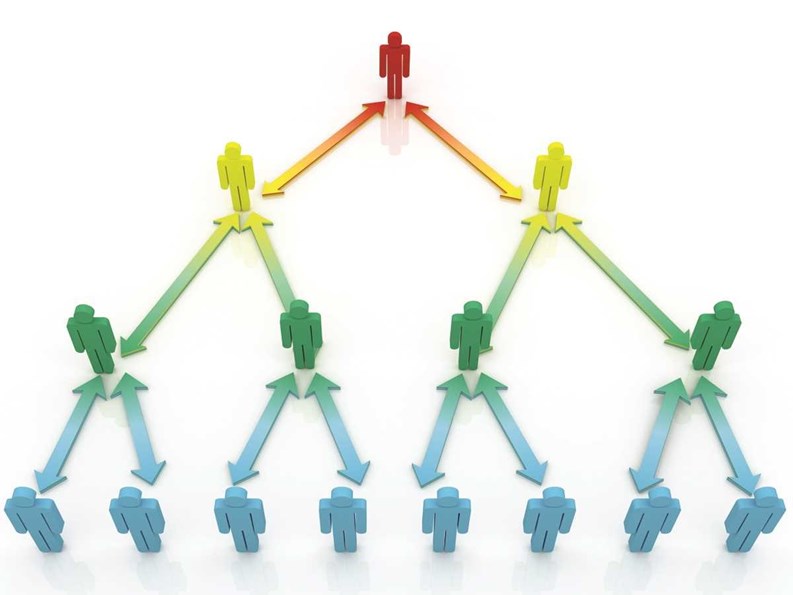

“A manager is always available, and staff members may go up the chain of command for problem resolution,” he says. “Employees need to realize they may need to break the chain of command and go up to the next level when their direct supervisor is part of the problem.”

Learning to Be a Leader

Lisa Northup serves as senior vice president of human resources for Associa, which has offices all over the United States, including locations in New York. Northup has worked in the HR field for 15 years. The most common challenge she observes among new managers is that they do not know how to be a leader. Stepping into a leadership role forces a manager to learn as they go, and for some this total immersion works, but it doesn’t work for everyone. Complicating this learning experience is the fact that what works for one property, probably will not work for all. Not only do new managers have to learn how to manage and to think on their feet in order to be fully successful, they have to learn to adapt and to be flexible to meet different needs.

Fortunately, Northup is attuned in her own position to recognize different learning styles and opportunities. Managers, and indeed all staff, are provided learning experiences through hands-on, on-the-job training, specialized training, the guidance of others, and feedback from management. There is always something to learn, and she feels skill sets can grow and adapt quickly in the right environment.

Staying on Course

Northup recommends that managers cultivate close ties and actively stay in touch with staff, so that they notice when fine tuning and adjustments are needed in any department or property. “HR efforts are team efforts,” she says. Communication is key to understanding what is going on, and a “hands-off” attitude will not serve. There are HR partners at all levels and a chain of command going all the way up to the corporate level. She agrees with Wurtzel that workers can jump over their supervisors. To facilitate this, Associa offers a confidential 'safe-line' that employees can call to report observations and concerns. “This is just one additional way to insure we listen to our human capital,” she says.

Stephan Elbaz, president of Esquire Management Corporation in Brooklyn, has his own formula for successful management. Ideally, he says, “A good property manager is someone that is extremely organized, detail-oriented, resourceful, and probably most important, a decision-maker.” He feels, however, that “it's not rocket science.” “Ninety-five percent of management is common sense—common sense, not losing your temper, and not panicking.” It's also good to have lots of contacts in the field and among vendors and to “maintain good relationships with residents, boards and vendors.”

The Power of Appreciation

One way to foster excellent staff performance, Elbaz advises, is to show appreciation. “Management is a business that has an overwhelming number of complaints compared to compliments. People never call you up and say, 'The heat is great, the elevator's clean, the laundry machines are working fine, the garden looks great. Thank you so much.' The complaint calls are very, very, very frequent. So managers are trained to have a thick skin. Many times people on the front lines—the porters and the superintendents and the handymen—don't have that same thick skin, and all they hear constantly are complaints;. 'I saw a bug, there's a cigarette butt that's been there for two days, the laundry machines are dirty, etc.' So one of the important things to do is to say thank you, and say it often. And tell people when they're doing a good job. Tell them that the building looks great, the floors are clean, everything looks nice, thank you. That doesn't cost a penny.”

Appreciation can be more formalized, too, says Elbaz. “In larger buildings that have a lot of staff, you can give an employee-of-the-month award. An award can be created on somebody's computer, with just the cost of a frame and some fancy paper, and the employee will hang it up with pride. In smaller buildings, it could be the employee of the quarter, or the employee of the season.” Recognition during the holidays is another way to show gratitude. “If you buy the staff a lunch, or even if you just bring in some pizzas and sodas to the building. A little thing at the end of the year. People remember things like that.”

Helpful Resources

And of course, avail yourself of continued learning. “The first resource I'm going to recommend is The Cooperator,” says Elbaz. “I would urge every managing agent to make full use of all of the valuable information and services they give from the annual Expo seminars to the monthly newspaper.” Elbaz also strongly supports the New York Association of Realty Managers (NYARM). “They deal strictly with managers. They're a 60-year-old organization that has monthly meetings and an annual trade show and offers many, many resources and classes to help managers.”

Elbaz reinforces the chain of command that Wurtzel outlines, likening it to the military rather than a baseball team. “Really,” he says, “the only time the board should get involved is from 30,000 feet.” When there's a problem, “The managing agent's job is to give recommendations and options to the board, to give them all the tools they need to make an informed decision. Then the board makes the decision, and the managing agent carries it out, always. The managing agent is the bad guy.”

On the other hand, Martin S. Kera, president of Bren Management in Manhattan and a 25-year veteran of the industry, has generally had a different experience. “We manage mostly small buildings with a staff of one super, or with a part-time visiting super. Usually we prepare a schedule for the super, but it is loosely managed. We usually work with someone who resides in the building to develop a schedule. If there are any issues, it is a combination of management and someone who resides in the building talking to the super.”

Although board involvement will vary, when it comes to managing human resources, the experts agree on numerous points. Start with a specific job description, hire good individuals, and let them do their jobs. Manage but don’t micro-manage; provide support, education, communication and motivation. Build a team and a chain of command whenever possible. Strong leadership, smart management and communication all help to make the most of a community's most valuable asset: its people.

Anne Childers is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator. Staff writer Judy Hill contributed to this article.

Leave a Comment