Imagine the biggest three-dimensional puzzle you can. Now imagine fitting eight million people into this puzzle. Putting the pieces together takes more than just luck. It takes enormous skill, precision and foresight. Those are three attributes that the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) works hard to cultivate—it’s their job to put that puzzle together and ensure that the people, buildings and infrastructure of all five boroughs meld together as seamlessly as possible. It’s not a challenge for the faint of heart.

Toward a Common Goal

The City Planning Commission, established by the 1936 City Charter, began operating in 1938 with seven members appointed by the mayor. The 1989 Charter expanded the commission to 13 members. The mayor appoints the commission’s chair, who is also the Director of City Planning. The mayor also appoints six other members, each borough president appoints one member, and the public advocate appoints one member. The chair serves at the mayor’s pleasure while the other 12 commissioners each serve for staggered terms of five years.

The DCP meets regularly to hold hearings and vote on applications, as described above, concerning the use, development and improvement of real property subject to city regulation. Its consideration of these applications includes an assessment of their environmental impacts where required by law.

More than 300 people work for the New York City Department of City Planning, all under the aegis of their chairperson, Amanda M. Burden. The department has staffed offices in Manhattan, Queens, Brooklyn, the Bronx and Staten Island, as well as a separate transportation division—a sign of how closely intertwined transportation, infrastructure and building are when it comes to creating a successful neighborhood or business district. “For the past six years with Amanda Burden, we have focused on strengthening the borough offices,” says Richard Barth, executive director of the department. “Those offices deal directly with communities by responding to community concerns.”

The department functions in conjunction with the City Planning Commission, a 13-member committee that includes Burden and 12 other individuals appointed by the mayor, by the five boroughs and by the public advocate. As stated on its website, the commission “[is responsible for] the conduct of planning relating to the orderly growth and development of the city, including adequate and appropriate resources for the housing, business, industry, transportation, distribution, recreation, culture, comfort, convenience, health and welfare of its population.”

“Our goal,” says Barth, “is to plan for the orderly growth and development of the city. City planning is the agency that shapes how this city grows.”

And what does that mean? It means it is up to the department “to plan for a growing population in a city built out to its edges,” Barth says. It means ensuring that there is mass transit access available to neighborhoods that need it and working to preserve the historical integrity of the city’s auto-dependent areas.

The department does not operate in a vacuum either. Burden, Barth and their staff work closely with City Hall and with other agencies and departments charged creating new business, building infrastructure, sustaining tourism and more. “We work closely to develop comprehensive strategies to advance housing and economic growth in the five boroughs,” Barth says.

To help sustain that cohesion, the department also recently resurrected the position of Chief Urban Designer, a post that had been empty for a number of years.

Making it Happen

The DCP believes in looking at the big picture. Each decision they make can trigger a cascade of results—some expected, some unexpected. That is one reason why they work from regional plans. “We put together plans that shape zoning, promote new jobs and create growth,” Barth says. They achieve this not only by working with other city officials and departments, but by listening to the people who live and work in the areas in question.

Over the past six years under Burden, the city has rezoned 6,000 city blocks in 88 neighborhoods, which is equivalent to roughly one-sixth of the city. This was done, Barth says, “in response to local needs. One of the reasons we’ve gotten so much done is because we’ve done these things in conjunction with community planners. We built consensus within each of these communities.”

That consensus has been achieved by talking with residents, business owners and elected officials, creating much-needed buy-in from the people whose opinions matter most: the folks who will spend their days and nights in these neighborhoods.

The city has worked hard, Barth says, “in terms of comprehensive planning, with advanced care given for the pedestrian environment and for preserving quality open spaces.” Attention to those kinds of quality of life details has helped give city plans a cohesion, Barth adds.

“It’s always difficult to juggle priorities,” Barth continues. “We wish we had more time to do everything and fulfill all the requests we get.”

The department also has dedicated itself to helping the city provide affordable housing to meet the needs of a wide range of incomes. The goal, says Barth, is to have “both market rate and affordable housing available.”

Under the guidance of Burden and Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, the department finds itself in a key role in achieving the goals of the mayor’s PlaNYC 2030 sustainability plan, promoting growth where mass transit can help reduce traffic, planting street trees, protecting and creating new green spaces. It’s estimated that the plan could help the city plant some 10,000 trees each year, going a long way toward reducing carbon emission issues in the city.

“We integrate green space into all our projects,” Barth says, “so that people will have a place to go and relax.” Especially in denser population areas, parks and recreational spaces are important because they give residents a place where they can stretch out and see the sun, maybe play catch with their kids. In short, it helps improve the city’s state of mind.

What the Future Holds

In addition to the department’s day-to-day operations and development, city planning is also involved in a number of significant projects that will have a large and positive impact on New York City as a whole.

For those who have lamented the decline of Coney Island, the city’s new plan aims to preserve the amusement area while creating new housing and business opportunities. “This area is so much ingrained in the city’s history,” Barth says. Its rejuvenation appears imminent, with a number of investors joining in to breathe new life into run-down or defunct spaces while simultaneously preserving an important piece of New York’s past.

Rezoning is also taking place on 125th Street in Manhattan as part of the five boroughs economic strategy designed to examine areas that haven’t been looked at in decades. The chief goal of the project is to enhance Harlem’s Main Street by creating incentives for the opening of small businesses and trying innovative things like bonuses for buildings given over for arts and entertainment purposes. Just as with Coney Island, the proposals are hearkening back to an important historical aspect of the neighborhood.

The Grand Concourse in the Bronx is another area seeing a great deal of change as rezoning has contributed to a redevelopment of the waterfront, making it more accessible to pedestrians and residents. “We’re a city of islands, and it’s surprising how much there is that needs to be done to connect people to the waterfront,” Barth says. In addition to walkways, the city is also promoting bike paths and other access points.

The DCP is also working with state and private landowners to remake Penn Station and return it to its original glory as an “extraordinary new transportation hub.”

Pillars of Planning

All of this activity is taking place within the framework of some pillars of planning that the DCP has adapted over the year. Their work is, in large part, about reusing land. Hardly a shock in a city of 8 million people where skyscrapers seem to skim the edge of the atmosphere and buildings are riding the river’s edge.

“Look at the Greenpoint-Williamsburg area [in Brooklyn],” Barth says. “It was industrial, blocked off and inaccessible to the public. It was a vestige of an industrial era that is no longer active.”

The department worked to connect those neighborhoods to other growing neighborhoods, taking underutilized land and transforming it through the judicious use of zoning laws and private resources.

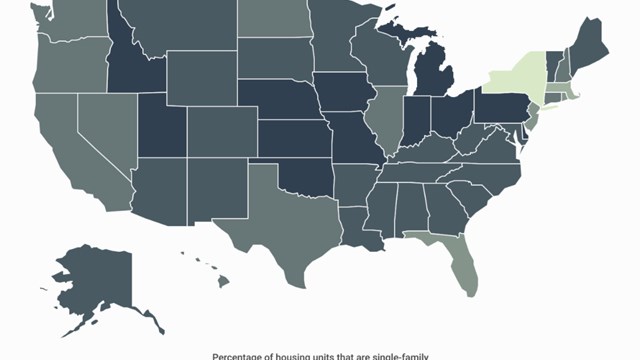

The department, Barth says, is “Intent on preserving the character of a lot of neighborhoods.” To do this, they use something called “contextual zoning,” looking at existing structures to ensure what types of new structures can be added—basically ensuring that the Empire State Building II does not get built next to a two-family flat in Queens.

For the DCP, it can be difficult to let the city’s residents know exactly what they do, which is an important factor in maintaining that dialogue that keeps projects flowing smoothly. “A lot of times, people don’t know what city planning does and how we can affect quality of life,” Barth says.

The department will continue to work toward its goal of creating a comfortable, thriving, accessible and green metropolis for residents and businesses. As it stands, Barth says, the challenges for the future will include handling population growth, providing housing for all incomes and encouraging residential building in areas where transportation is readily accessible or can be added.

Liz Lent is a freelance writer and teacher and a frequent contributor toThe Cooperator.

Leave a Comment