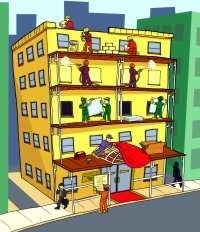

Every time a co-op or condo building needs exterior work - an occurrence more regular now than a quarter century ago - a group of highly-trained, highly-specialized, and extremely brave professionals arrive to carry out the project. They set up scaffolding, lower swinging platforms, use heavy, often dangerous, equipment and supplies with the goal of providing a façade facelift or complete overhaul.

Just as New York's landscape continually changes, so too have the exterior maintenance trades. Heights have escalated, materials have changed, regulations have become far stricter, and the pace of work in a hot real estate market has multiplied. For boards and managing agents faced with a façade refurbishment project, it's a smart idea to get an understanding of the regulations and the players - and their training and licensing - who will be involved in the project.

Building History

In 1979, a piece of terra cotta masonry fell from the facade of an Upper West Side building and killed a passing college student. This tragedy provided the impetus for the city to take action to redress a glaring deficiency: the lack of oversight over building exteriors.

"It used to be that the decision to make repairs to the façade was the decision of the individual buildings and owners," says Michael Grant of Accura Restoration Inc. in Astoria. "Obviously, this didn't work very well. If you were on Central Park West, or on Park Avenue, they took care of the building," he says, but otherwise, not so much.

The city government that often moves at a glacial pace reacted swiftly and decisively, enacting Local Law 10 the following year, 1980. The new law, known as Local Law 10/80, required buildings to fix unsafe facades as soon as discovered, among other new rules.

"Local Law 10 of 1980 required periodic façade inspection to be performed by a licensed engineer or registered architect," according to Alan Epstein, president of Epstein Engineering and an expert on building exterior city regulations.

While certainly a step in the right direction, 10/80's requirements weren't stringent enough to provide real change. For one thing, the law called for a visual inspection of the front of all buildings taller than six stories. In practice, this meant that the inspector had to stand in front of a skyscraper and look up - not a very effective way of spotting potential problems on, say, the 52nd floor. For another, only the fronts of the buildings were inspected. The other three sides could be crumbling to bits and legally the inspectors could do nothing about it.

"In 1998, the law was updated," Epstein explains. "Local Law 11 of 1998" - 11/98, in the industry parlance - "expanded the regulations. They decided that inspectors would perform [checks] on all façades - sides, back, front. In addition, a minimum of one scaffold inspection of the street façade was required."

That was one major change. Another regulated the speed by which repairs had to be made. Before 11/98 passed, only conditions deemed "unsafe" by the inspectors had to be repaired immediately - the other two designations, "conditions in need of repair" and "maintenance items," could be deferred indefinitely.

"In '98, maintenance was put on a timetable," Epstein explains. "Now you have five years to complete all required maintenance." The updated law established a standard maximum five-year reporting time for each successive "critical examination" of a building.

"The laws are cyclical in nature," Grant says. "They come out every five years. Exterior contractors are in demand because somebody has to do the inspecting."

If the law is cyclical, that means a change might be in store. When will Local Law 11/98 be updated, and what might it include?

"To speculate on the future," Epstein says, "a new law might include smaller buildings to be inspected, buildings under six stories in height." The existing law, he explains, doesn't apply to brownstones, for example, although many brownstones, because of their age, could be in need of façade repair.

Epstein is quick to point out that his speculations come from chatter among people in the industry, and not from officials at City Hall. He feels there is no mad rush to amend Local Law 11/98. "The law is effective in its current format," he says.

Local Law 10/80 and the subsequent Local Law 11/98 may have been something of a boon for industry businesses. Prior to the requirements being written into law, there was always façade work to be done on the city's thousands of buildings, but it was more sporadic, typically dictated by emergency rather than maintenance. Now, exterior maintenance professionals all along the spectrum of services say they have no shortage of projects - someone has to rig the scaffolds for all those building façade inspections, someone has to fix whatever problems are inevitably found, and someone else has to cart off the construction debris from repair projects.

There are dangers to the added workload, however. "[The industry is at an all-time high with accidents," says Wayne Bellet, owner of Bellet Construction in Manhattan. "Last year there were 15 incidents where there were scaffold failures, and people got seriously injured or died. The year before that, there were three to five."

He attributes this to a labor shortage problem: the amount of work has compelled some companies to cut corners.

"The change is indicative of the increased reliance on poor labor," he says. "People are being put up there that aren't trained, in spite of the regulations."

The nature of the business - uncovering what was glossed over years ago - also means that what started off as one type of project can quickly morph into something altogether different.

"Generally, in this line of work, the jobs that we bid can become larger during the course of the job, because you don't know what you'll find," Grant says. "You don't have a stable base. If someone has to install a roof, you know what that involves. But you have an unknown quantity under the façade."

The job has changed through the years. The technology is better, but the workload is heavier, and the requirements more daunting.

"The regulations are intense," Bellet says. "That was not the case years ago."

Who's Out There?

The people doing work on the exterior of a building represent a diverse group of specialized skills - waterproofing, roofing, masonry, and anything else related to the exterior of a building. Plumbers and electricians are also sometimes involved, albeit less frequently. "It's kind of a hybrid," says Bellet. "It's what engineers call Division 7 work - masonry, roofing, anything to do with the envelope of a building."

What most façade jobs have in common is simple: they need to be performed on scaffolds, often hundreds of feet in the air, in the baking heat of summer and extreme cold of winter.

According to Bellet, there are divisions even among already-specialized trades, and adhering to the rules and regulations governing those trades is of paramount importance. Consider riggers, for example. They're the ones charged with lifting extremely heavy loads of materials, workers, and pieces of equipment from sidewalk level up the side of the building to where the work is being carried out. Rigging is a very specialized trade, and makes use of custom-built equipment as well as huge pulleys and crane apparatus. Unlike most other trades today, rigging is a skill that is learned by apprenticeship. Because of the dangerous nature of what they do, riggers must be scrupulously trained, experienced, and licensed to do the level of work necessary for a given job.

"There are two types of riggers," says Bellet, "'special' and 'master.' Special riggers can lift weights up to 1,500 pounds. Over that, you need a master rigger." Master riggers, then, are the ones operating the cranes. Most co-op and condo buildings will only need to employ a special rigger for its purposes - but regardless, he or she had better be properly licensed and fully insured.

Some of the exterior trades are the bailiwick of Local 32BJ, but generally only for large commercial jobs, such as the construction of an entirely new building. "The union doesn't exercise power over all exterior trades," Bellet says, noting that most work done to most existing co-op and condo buildings is non-union in nature.

Grant agrees. "We were never union," he says, "and that's acceptable in the restoration market."

Aiming To Climb

So how does one become a something like a rigger - master or otherwise? "Many of the companies are family owned," Grant says. Bellet, for one, followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. "More trades than you can imagine are driven by multiple generations," he says.

Those that are not going into the family business tend to have friends who work in the industry, or some other way in the door.

"You have someone, a young man, who's mechanically inclined," Bellet says. "He applies to be a laborer. During the course of three to five years, he's gradually trained in all the flavors of what we do."

Grant was a contractor who specialized in restoration work. Getting his riggers license was the next logical step - though certainly no piece of cake. City regulations require five years of experience working on rigging scaffolds before a worker can get a license to operate one himself. Even beyond that, the vetting process is rigorous: riggers must be fingerprinted and photographed, they must prominently display their company logo when on the job, and they must have a certificate of physical fitness.

It also helps not to be afraid of heights.

"My eight-year-old son has shown signs that he is," Bellet says, with a chuckle, "but not my six-year-old daughter. So who knows? The next generation might be run by a woman."

Leave a Comment