The day-to-day costs of running a multifamily residential building are significant. There’s the fuel oil, electric, cleaning supplies, equipment maintenance and service calls for repair and upkeep. Then there are the insurance costs, landscaping, trash removal, snow removal, advertising, property taxes, and maintenance fees.

In today’s economy, the cost of many of these expenses have gone nowhere but up (and up and up…). For example, Jerry Blumberg, CEO at Kew Forest Maintenance Supply in Woodside admits that in his industry, the supplies costs are going ‘through the roof.’ And after one of the harshest winters in a long time when fuel costs escalated, most businesses are just raising their prices just to keep up with their own rising expenses.

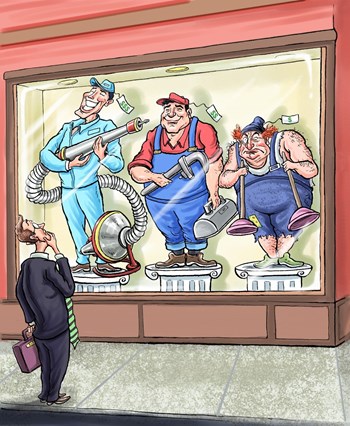

Costs should always be on the forefront of a manager’s mind, and there may come a time when like it or not, the budget simply has to be tightened. The bottom line to managing a building’s bottom line is to do what anybody does when facing more month at the end of their money—evaluate spending, cut costs and look for better deals.

Evaluate Spending

Evaluating current spending is the first step in determining whether or not any spending is out of control and if changes are needed to rein things in, says Robert Serrara, management director at Anker Management in Hartsdale. Several times during the year, he and his managers review their buildings' budgets. “We go over the year prior, and now we’re doing that more frequently because of the costs going up,” he says. “We’re always watching, especially with the kind of economy we’ve been in.”

When it comes to ordering supplies, Anker’s managers keep a running log of what the supers in each building need. “As the super goes over items in the building, say on a monthly basis, we can see what is being used more frequently,” he says.

Bram Fierstein, president of Gramatan Management Inc. in New Rochelle does business with a building goods supplier who emails a copy of a preliminary order to the company before it is finalized. This allows Fierstein an opportunity to review the purchase order and speak with the super if necessary before the final order is placed.

“Once supers know you are monitoring their orders this way, the size of the orders tend to be reduced,” he says. “Supers love to order cases of supplies because that's what the vendor wants, but it's better to instruct the staff to only order what will be used within a given month. You don't need twelve gallons of Windex if you only use three gallons a month.”

Fierstein also explains that he had a board member who was very concerned about how much was being spent on supplies, so he wanted to be involved in evaluating purchases at the grassroots level.

“We developed an order sheet that the super had to complete and give to the board member for approval,” says Fierstein. “While the savings were modest at best, the board and staff were at least satisfied that money was not being wasted.”

During the review of all expenses, current numbers should be compared to a year, or even just a few months ago. What costs have gone up? Is the super suddenly buying more of the same maintenance supplies? If so, why?

And smart inquiry doesn't just stop with glass cleaner and mop-heads. “Ask common sense questions too, like why are you paying overtime and what can you do to reduce that?” says Stephen Beer, CPA and a partner at Manhattan-based accounting firm Czarnowski & Beer, LLP.

Cut Costs and Earn Money

If your expense reviews do turn up areas where there is excessive spending, look to cut costs. While some buildings prefer to operate on a buy-as-needed basis, others find that purchasing supplies in bulk can help save some needed cash. “For example, we don’t buy our energy-efficient light bulbs from standard vendors; we purchase them in bulk online,” says Serrara. “We’ve done this with other items as well, and we’ve seen a real savings through that.”

For some buildings, buying less, instead of in bulk, might save money. “Inventory control is very essential,” says Serrara. “We have a list of what the super has in stock and what was on his last order and what his next order will be. We have as tight a control as possible.”

“With prices changing, every day I’m getting letters from manufacturers that their costs have gone up 3 to 10 percent,” says Blumberg. “Management has to check what is being bought and how much.”

Blumberg suggests that managers also know what they are buying. “For instance,” he says, “plastic bags are a major item that supers buy. They're sold by the pound, but are often bought by the case—and nobody knows what a case weighs, and whether they are getting the full amount that they're paying for. So they need to weigh the cases to make sure they are getting what they are paying for.”

Ya Better Shop Around

Another way to cut costs is to shop around and compare current vendors' prices with those of their competitors. For example, say it's springtime, and you’ve been chatting with the manager of another building in town. You find that your landscaping contract is a little pricey compared to others in the area. So you do a little research and find a great new vendor who is less expensive than the one you use now, but who provides a comparable level of service.

“If we see a difference in price, the board might say ‘But we’re happy with our landscaper,’ and instead you might ask the current landscaper if they will match the price,” says Beer. “Sometimes it comes into negotiation that if he is willing to meet the price he can keep your account. If the contractor is familiar with property, of course it makes the process a little easier, with fewer headaches for the residents of the property, but ultimately it comes down to the quality of the work and the price.”

To compare your building’s operating costs to what other buildings are paying, check out The Comparative Study completed by The Council of New York Cooperatives & Condominiums (CNYC). According to the CYNC, the study is a benchmark to help cooperatives and condominiums determine how well they have budgeted for operating costs. The analysis examines the various costs of operating a building and analyzes all information on a per-room basis, beginning with the property tax assessment and mortgage figures for participating buildings and the amounts paid as maintenance or carrying charges.

The study then lists amounts spent per room on wages, fuel, utilities, repairs and maintenance, insurance, management costs, administrative costs, water and sewer fees, property tax, and debt service. When possible, elevator maintenance and legal and accounting costs are each listed separately. The study then incorporates this basic information for the year into a ten-year chart of summary statistics, where it calculates the average and median per-room, per-year outlay for each item, and the average portion of total operating budget devoted to each. .

“You want to be part of that financial statement,” says Beer, whose company provides audits of a building’s expenditures, such as utilities and insurance. “You can look at your expenses, compare them to other buildings and see where you’re out of whack.”

Like every budget, cutting costs is only half the battle in a tough economy. All the experts here said if times are tough, managers should be working on bringing in more money as well. To do that, they suggest thinking out of the box.

“Take early action on arrears,” says Beer. “You’re not nickel-and-diming, but the earlier you move on it, the better.”

In today’s economy, vendors also welcome customers who can pay their bills on time and they are even willing to reward it. “Some vendors are giving us discounts when we pay our bills within a 30 to 60 day period,” says Serrara.

For example, Serrara also explains how New York City management companies that pay the water bill online can receive a two percent discount. “We watch our water consumption very closely and we can see if there’s an issue,” he says. “If the water bill is $100,000 and you pay your bill on time, your discount is $2,000 which can offset some of the fuel costs or you can use it for supplies.”

“To increase income coming into the building, we were approached to film a TV pilot in one of our properties,” says Serrara. “We negotiated a substantial sum of money for the property—low five figures—and it was little inconvenience for the shareholders. Now we’re in touch with companies that scout for locations.”

Just as anyone would do with their own personal financial accounts, a building’s financial accounts should be checked and double checked to make sure they’re getting the best bang for the buck.

Lisa Iannucci is a freelance writer and author living in Poughkeepsie, New York and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment