In April of 2017, The Cooperator examined the passive house building standard that, according to the Passive House Institute U.S. website, follows a set of design principles to achieve energy efficiency in a structure–or as the organization puts it: “Maximize your gains, minimize your losses.”

The principles involved in the design and construction of a passive house building are:

- "Employs continuous insulation throughout its entire envelope without any thermal bridging."

- "The building envelope is extremely airtight, preventing infiltration of outside air and loss of conditioned air."

- "Employs high-performance windows (typically triple-paned) and doors."

- "Uses some form of balanced heat- and moisture-recovery ventilation and a minimal space conditioning system."

- "Solar gain is managed to exploit the sun's energy for heating purposes in the heating season and to minimize overheating during the cooling season.”

In the past year, there have been a few notable passive house-related developments. For starters, the Sol Lux Alpha condominium development in San Francisco marked that city’s first passive house-certified, net-positive multifamily property. Developed by Lloyd Klein and John Sarter of Off the Grid Design, the six-story, four-unit luxury condominium building was, according to Sol Lux Alpha's advertising, “designed to consume 80 to 90 percent less energy for heating and cooling than a traditional home.”

As one might imagine given its moniker, much of the efficiency of Sol Lux Alpha is thanks to its numerous solar panels, which provide excess energy that is then stored in batteries and can be used to keep the building running for an extended period of time. Units range from a cool $2 million to an even cooler $3 million.

Here in New York, construction is underway on what will become Manhattan's second-tallest passive house building (behind Cornell Tech's Roosevelt Island dormitory): a 24-story, 55-apartment residence at 211 West 29th Street in Chelsea. Designed by ZH Architects and developed by Bernstein Real Estate, the project is expected to finish before the end of 2018.

And then there's Sendero Verde in East Harlem, a mixed-use, multi-building project in the making, which will contain 650 affordable residential units, athletic facilities, a pool, a charter school, and ground-floor retail. Spearheaded by Handel Architects, the development is being touted as the largest, affordable passive house building in the world.

Local Scene

Along with co-ops, there have also been local condo projects over the past few years that have adhered to this ambitious energy benchmark.

For instance, there's the R-951 Residence, which is not only the first passive house condo in Brooklyn, but the first building to achieve the Net Zero Energy Capable certification set by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. The design by Paul Castrucci Architects features three 1,500-square-foot duplex condos, a 1,200-gallon rainwater collection system, and a rooftop solar energy system. Individual residences each offer a deck, backyard, and gardening space.

Then there's the seven-floor building at 255 Columbia Street on Brooklyn's waterfront, where HPI Development introduced 13 two-, three-, and four-bedroom condos to the market in 2014. Each unit features a constant supply of filtered air via individual energy recovery ventilation, and the property offers a 2,000-square-foot common garden, along with a private outdoor space for each residence.

According to architect and president of New York Passive House, Andreas M. Benzing, the New York Housing and Preservation Development office often mandates in a request for proposal (RFP) for new residential construction that the properties be built to passive house certification, while for-profit developers are less beholden to any such limitations. This is why passive house multifamily may skew more toward the rental side in New York City.

Passive House: The Book

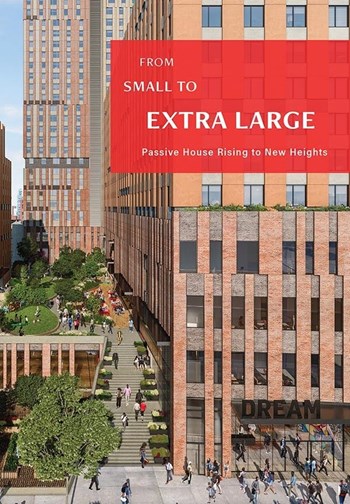

Many of the aforementioned projects are featured in From Small to Extra Large: Passive House Rising to New Heights, the first e-book guide produced by Passive House Buildings, detailing over 50 works that were built to the energy standard. And in June, the organization held what Benzing called “our biggest conference yet, with nearly 600 attendees and 38 expo booths.”

Going forward, Benzing is cautiously optimistic about passive house as a means to offset citywide energy use intensity (EUI). “It's the overall energy which a building uses, including production and transport thereof, per year,” explains Benzing. “And currently a multifamily building tends to have an EUI of 200. The mayor's office says that needs to come down to an average of about 84 per building. And passive house actually goes so low as 38, which is why we're shooting for new construction with much lower EUI than what is necessary, in order to counterbalance certain buildings that won't be retrofitted in time to make the target greenhouse gas reduction of 80 percent by 2050, as established by the Paris Agreement in 2015.”

Given how often the goalposts move on climate change benchmarks – and given the Trump Administration's apparent lack of enthusiasm\ in this area – it's fair to have a healthy skepticism about the future. But passive house certainly appears to offer a model that ensures that new projects are doing more good than harm to our environment, which is encouraging.

Mike Odenthal is a staff writer at The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment