Just take a walk around the streets and parks of the city, and it’s easy to see that New Yorkers love their pets. But not everyone loves animals, of course—and this can be problematic when it comes to a board deciding if pets should be permitted in their building.

“Boards allow pets because many shareholders and unit owners want pets,” says Lynn Whiting, director of management for The Argo Corporation, a Manhattan-based residential property management firm. “It's a quality of life issue, and of course many board members are animal lovers/pet owners themselves. Many owners may have specifically decided on purchasing in a particular co-op or condo because it is pet-friendly.”

Although the data isn't officially kept, many real estate agents in the city estimate that about 50 percent of the co-ops and condos in New York City are pet-friendly. Yet every building has its own requirements and set of circumstances that makes it unique.

“Each building decides for itself what their pet rules are going to be, but there’s not a hard-and-fast set of rules by any stretch of the imagination,” says Barbara Fox, president of Fox Residential Group, a residential brokerage located in Manhattan. “Every building is different, but I think the fewer restrictions a co-op or condo puts on the tenant, the more people are likely to be attracted to the building.”

“One big benefit when you have people who have pets [living in your building] is that pet owners are often very joyous, happy people,” says Linda Cohen Wassong, a broker with Prudential Douglas Elliman who often matches luxury clients with pet-friendly buildings. “It’s always a benefit to have people who live in your building from all walks of life and diversity.”

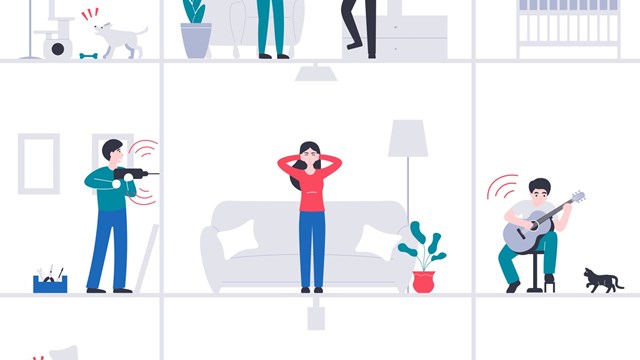

Not that disallowing pets makes a building undesirable, of course. All boards must take things into consideration regarding their residents' safety and peace of mind. Maybe there is only one elevator and residents would be hesitant about riding with a dog. Perhaps several people are allergic to cats. And of course, you have to factor in the noise that a barking dog or dogs can create.

These are just some of the things that boards and management must consider to balance their residents’ right to keep companion animals versus the impact those animals can have on value, maintenance, and community relations.

Making a Decision

When it comes to pet problems, a large percentage deal with dogs, and to a lesser extent cats, since those two species make up most of the pets in the city. Still, rules should be in place concerning other animals as well. Snakes can scare people and birds can be noisy while things such as gerbils or rabbits may be considered OK. Some buildings want to meet the pet and conduct “an interview” to see how they are around people, how big they are and if they are noisy. This is a good way for boards to decide what works for their situation. Some boards may tack on things such as weight restrictions—say 25 lbs.—in an effort to manage the behavioral issues associated with pets.

“There was a time when we did not allow pets, but I was able to convince the board that in our particular situation, it would be a good thing to allow them,” says Bob Friedrich, president of the 134-building, 2,904 garden apartment Glen Oaks Village cooperative association in Queens. “We felt that after speaking to our residents and getting a consensus, and bringing the board and residents into the process, we should change the house rules to permit pets.”

Money Matters

One big consideration for Glen Oaks Village making the change to allow pets concerned property values.

“We felt that since most co-ops in this area do not allow pets, by offering something that others don’t, it would help. The property values have held stronger here than in other communities, especially during this real estate crisis,” Friedrich says. “We feel we made the right decision.”

That seems to be the case around Manhattan as well. Buildings that allow pets seem to be more attractive to many.

“It’s a great thing for buildings to do because they can command more in terms of money because people will pay more to live in buildings where they can have a pet,” says Wassong. “You may get buyers more interested because they allow pets, so there is a target audience.”

Fox is also founder of a dog rescue organization in Manhattan named Woof Dog Rescue, so she often deals with clients who are searching for pet-friendly homes. Four years ago, Fox and her husband were looking to move into the city with their four dogs and two cats and found it wasn’t easy to find a place to live.

“There were so few buildings that were receptive to four dogs and two cats, but I did a major search for those that were, and I was able to find what we were looking for,” Fox says. “I know the buildings, so I could find one—but not everyone would have such a successful search.”

Rules and Laws

New York City pet laws concern situations such as picking up after your dog, requiring leashes and adhering to noise ordinances. New York City through its Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) also expressly forbids residents from keeping non-domesticated animals as pets.

According to Whiting, “The Department of Health prohibits wild animals of any kind—the list is endless. The reason is for public health and safety, the most compelling health reason is that wild animals can have rabies. The DOHMH strictly enforces pet laws, but they have to rely on people to notify them when a wild animal is being harbored. In response, the DOHMH takes immediate action to remove the animal.”

Tigers, macaques, and cassowaries aside, condos and co-ops that allow pets usually have their own set of rules regarding specific animals. For them, the pet laws aren’t just guidelines, but are taken very seriously by both residents and management.

“The rules are so strictly enforced, it’s like the animal police,” Wassong says.

By having a set of laws similar to the New York City pet laws concerning picking up after your dog, controlling barking and being a nuisance, boards will have an easier time in court if they need to remove an animal for violations.

“Now that we have house rules in place that mirror the city laws, if someone is not obeying the house rules and get more than two violations over a one year period, we can take them to court,” says Friedrich. “We have already won six cases in which the resident is no longer permitted to harbor a pet. It really makes it a better environment now, because we can control the situation a lot better.”

Although a pet will be grandfathered in if a building later decides to disallow pets, if that animal dies, the owner can not get another.

“If something changes in your house rules, you can not replace your pet,” Wassong says. “Everyone knows how much people love their pets; people buy in buildings because they can have pets—so if a rule changes, it can be so devastating to the people that they will eventually give up their homes.”

Getting Around the Law

Even when boards have set rules that disallow pets in a building, there are still two ways for a person to legally harbor a pet.

One involves New York and federal laws that prohibit discrimination against those with disabilities. People who are in the need of seeing-eye dogs or other animals for help with a disability may keep these animals in their homes, regardless of the house rules. This also includes allowing companion animals as pets that provide the service of emotional support to their disabled owners.

Fox says that the reality is that if a person wants a dog and can get a letter from a doctor saying they emotionally need a dog or an animal, a board may have a tough time saying no to that. She cites a recent example from one of her clients.

“We had a situation recently where a man was living in a co-op where you couldn’t have pets over 20 pounds,” Fox says. “He got a dog that was 30 pounds, and he got a call from the board immediately telling him to get rid of the dog. But he truly needed the dog. He was a widower and was very lonely and his doctor suggested that he get a dog, so he got a letter from the doctor and [the board] approved it.”

If they refuse, the co-op board could be liable for compensatory and punitive damages in state or federal court, as well as hefty fines which may be levied by such regulatory agencies as the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, or the City of New York Commission on Human Rights for failure to grant reasonable accommodation to a disabled tenant.

Pet Law 101

Another way for people to get around no-pet buildings is in what people in the industry call “The Pet Law,” which states that if a landlord fails, within three months of knowing about a tenant's “open and notorious” harboring of a pet, to enforce any applicable “no pet” provision, then any such provision is deemed void.

Enacted in 1983, the New York City Pet Law (Section 27-2009.1 of the New York City administrative code) says that if a resident in a building with three or more units harbors a pet openly and notoriously for three or more months, and the owner or building employee has knowledge of the pet and fails to commence an action or proceeding in court within three months of notice of the pet, then any no-pet clause is deemed waived and unenforceable.

The law applies in New York City. Westchester County has a similar law (Westchester County Law § 695.01 et seq.). Pet owners living in buildings with fewer than three units do have other defenses that have worked on behalf of pet owners prior to the enactment of the law. Shortly after the Pet Law was passed, it was found to be applicable to cooperative apartments. There are conflicting legal interpretations, however.

An appeals court covering Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island and Westchester ruled that it also applies to condominiums but the appellate court covering Manhattan and the Bronx has ruled that it does not apply to condos there. Although the law applies to co-ops throughout the entire city, it only applies in condo buildings in the 2nd Department, which encompasses Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island.

Some tips to prove existence of an animal include taking photos of your pet in the building, making sure your neighbors see the pet is living there, keeping a log of any communication with building employees about the pet or saving any complaints from the board pertaining to the animal.

“The New York 90-day rule means that if someone is harboring a pet for more than 90 days in plain view of the management or its employees, the pet is considered to be a legally-harbored pet,” says Friedrich. “What happens is a lot of people have pets and they may walk them and have them for 90 days, and if a co-op then tried to have the owner remove their pet, there would be a court battle and ultimately the co-op would lose.

This is an expensive process and you can’t keep paying resources on battles you are not winning.”

Under current New York City Pet Law, there is no requirement that says you need to have permission of the landlord prior to introducing a pet into the home.

Staying Neighborly

Not everyone loves animals, and pet owners should keep this in mind when walking their animals through their buildings, on elevators and on the streets nearby. And even for avowed, lifelong animal lovers, a dog that barks nonstop while their owner is away at work all day is simply maddening.

“Without a doubt, the most common problem we encounter is dogs that bark while their owners are away,” says Whiting. “It's a real nuisance, and not an easy problem for a pet owner to resolve. To a lesser extent there have been issues with dog walkers bringing multiple dogs into the building, or residents who are uncomfortable when they encounter dogs in the elevator or common areas. With house rules that address these possible problems, however, they're manageable.”

“I believe in responsible pet ownership,” says Wassong. “Pet owners should do everything they can to make it easier for everybody in the building. Before getting on an elevator with a dog, the owner can ask those inside if it's O.K. There are things you can do to make it a friendlier world.”

Sometimes, it’s up to management to make help the pet owners and non-pet owners live in harmony together.

“You have a group of pet lovers and those not crazy about pets, so what you have to do is make a strong effort to communicate with residents, enforce house rules and make sure people know they are being enforced,” Friedrich says. “If you can deal with issues, and people know that you're dealing with them, I think you can achieve peace among residents and between residents and pets.”

Keith Loria is a freelance reporter and a frequent contributor toThe Cooperator.

7 Comments

Leave a Comment