One of the trickier problems to deal with when you live in a co-op or condo is dealing with board members who sometimes let the power go to their heads. Even though they are entrusted with a great deal of responsibility in the smooth running of the building, it’s vital that board members don’t use their position to create a situation where they are setting themselves up for a conflict of interest dispute.

“We have seen conflicts of interest arise in cases where a board member owns, is employed by, or in some other way represents, a goods or service company that wishes to do business with the building,” says Michael Berenson, president of AKAM Associates, Inc., providing on-site management to New York co-ops and condos. “We have also seen conflicts of interest arise where a board member is a real estate salesperson or broker and wishes to transact business with the building.”

In these cases, the board member stands to profit financially from mixing his or her two interests and may be tempted to put the interests of the business ahead of the interests of the building. When that happens, the board member runs the risk of breaching his or her fiduciary obligation to the building.

“It’s a very dicey issue because there are no hard and fast rules and that’s a problem,” says Andrew P. Brucker, Esq., a partner with Schechter & Brucker, P.C, a law firm in Manhattan. “Even the appearance of impropriety—even if no conflict of interest has occurred—is something that boards need to look out for.” And nothing undermines a community’s faith in their leadership faster than things like impropriety and self-dealing amongst the board/management team, or even the implication that these things might be going on.

Avoiding Problems

Living in close proximity to others, along with a sense of loss of control, gives rise to a whole host of different types of disputes. Adding a conflict of interest problem into the mix can make the situation even more volatile.

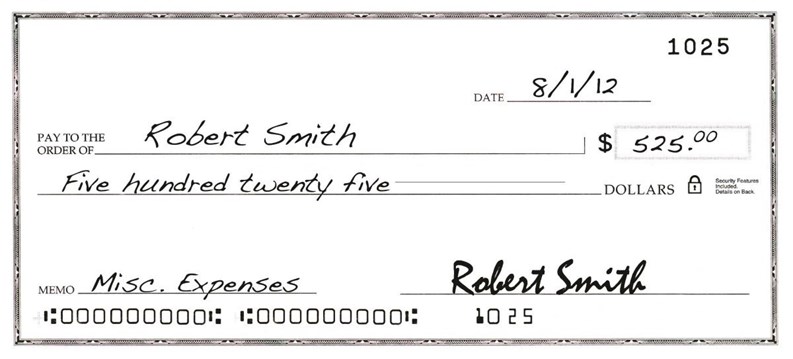

“The most common are most obvious, where a board member is getting favored treatment one way or another,” says Larry Simms, president of the Alliance of Condo & Co-op Owners. “It could take the form of free work being done by vendors, could take form of work being done by staff, could be gifts ranging from bottle of scotch to getting premium cable services without paying for them. I have even heard of cases of banks as an inducement giving favorable loan deals.”

Common sources of conflicts of interest are directors who directly or indirectly are connected to companies that the association may currently use or consider hiring.

“Boards and managers should be absolutely certain that there is an arm’s-length relationship between the contractor and the building,” Berenson says. “This means that the contractor has no financial, personal, or other interest in the building besides the immediate contract, and likewise that no member of the board or management has any financial, personal, or other interest in the contractor besides the immediate contract.”

Some board members try to get away with having pets in a no pet building, having jobs done for free (such as landscaping) in exchange for hiring a contractor, or hiring friends or family to do something in the building. Some examples include a board member allowing an unlicensed painter to work in his apartment or approving a sales application that otherwise might not be approved.

Other conflicts of interest are not as obvious as the examples above. Perhaps the association is trying to decide if they wish to pursue a noise violation when the only complainant is a member of the board who lives next door to the accused violator.

In this case, the director with an interest at stake would be best served by disclosing that interest, making his or her case to the board in the same manner any other owner would and then letting the rest of the board vote on the matter.

Brucker says that something very common in co-ops and condos is the use of a broker for insurance who is related to the management company.

“If they are supposed to advise you on things but are an affiliated company, would one arm rat out another arm?” Brucker asks. “It’s the manager who usually looks out for the board’s interest, and this could cause a conflict of interest.”

Follow the Law

Because New York State Business Corporation Law (BCL) prohibits conflicts of interest in which an individual profits financially or otherwise by exploiting his relationship with a co-op or condo, such behavior could void the board member’s protection against liability as provided by the building’s governing documents and/or by the building’s directors and officers liability insurance.

“If the act is of significant magnitude, lawsuits and criminal charges also are possibilities,” Berenson says. “In terms of day-to-day consequences, the unlicensed contractor who is a family friend of a board member and who was allowed to work in the building by that board member may not seem like a big deal at first … but both the board member and the contractor will be liable should the contractor inadvertently break a riser in the course of his work in the building.”

The best rule of thumb for everyone—for the board member, the manager, and the building—is to avoid all situations in which even the appearance of a conflict of interest is present.

Cause and Effect

Conflicts of interest that are either overlooked or allowed to continue can create real damage to community morale as well as to undermine the credibility of the governing board.

To help clients avoid conflict of interest issues, a manager should be conversant in the regulations articulated by the BCL, which governs co-ops and condos and specifically addresses conflict of interest. As well, the manager must be familiar with the co-op’s or condo’s documents and bylaws, which also will likely address conflicts of interest.

“Additionally, a past board may have established policies regarding conflicts of interest in the building, and the manager should be aware of these policies and remind the board of them,” Berenson says. “Beyond knowing the building’s governing rules, managers can help their boards avoid conflicts of interest by strongly encouraging board members to disclose any relationship they may have that could potentially pose a conflict of interest.”

When certain conflicts of interest occur, it’s the community that suffers. As an example, if a management company has a financial interest in a vendor, not only is it hard to be sure that the association is getting the best pricing, but if that vendor is failing from a performance perspective, it is not in the management company’s best interest to recommend a change as they will be losing business.

When Simms became president of his condo board, he learned that a Christmas tree vendor was providing free trees to the board in exchange for being able to set up shop on the sidewalk. To avoid a conflict of interest mess, Simms instead negotiated a 20 percent discount for all residents, so that no one was getting special treatment.

Family Matters

Let’s say a board member acting in good faith hires a family member to do interior maintenance work in their building and something breaks. This is a serious problem that you are better off not even giving yourself the chance to get in.

“The immediate situation should have been resolved before the family member started working in the building by the board member disclosing to the board his relationship with the individual,” Berenson says. “If this was not done and a problem arises, the contractor should be removed from the building immediately and the board member may be asked to relinquish his officer’s position and/or to step down from the board.”

In these cases, the building must be made whole, and legal intervention will be necessary to determine where actual liability rests and who needs to compensate the building. After going through such a situation, boards would be well-advised to establish clear policies and boundaries with regard to board members and conflicts of interest in the building, and then to enforce those policies and boundaries uniformly moving forward.

“We preach stay out of conflicts. Full disclosure is very important,” Brucker says. “If there is a conflict, not only should they not be involved in the vote, but not involved in the discussion at all. Those other directors shouldn’t have to watch their words just because you are there.”

Boards who learn the hard way—either through criticism or in the most extreme cases recall from the board—that hiring a family member or friend was a bad idea from the get-go, often don’t repeat the exercise.

“You should ask yourself, ‘Will this raise any eyebrows?’ But if you need to ask yourself the question, the answer is probably already, ‘yes,’” Simms says. “Sometimes you might have a vendor with special skills and there is no alternative, and in this case, you should make the recommendation, disclose the nature of the connection and then recuse oneself from the final decision.”

Keith Loria is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment