Though many co-op buildings forbid subletting for an array of reasons, some co-op (and many more condo) buildings have populations of rental tenants residing in them. The arrangement is mostly peaceful and drama-free, but friction does occasionally arise between rental tenants and fully vested shareholders, often over issues with house rules or conflicts between neighbors.

It’s important for boards and managers to familiarize themselves with what rights and responsibilities co-op/condo subtenants have, and to uphold those rights under the law.

By Definition

First, let’s define our terms. A sublessee, strictly speaking, is someone who leases an apartment from a unit owner or a shareholder living there. A sublessor is the unit owner or shareholder who seeks to sublet the apartment through a sublease arrangement.

The semi-mythical “illegal New York sublet” is usually a third party renting an apartment from a rental tenant, who is usually renting at a plum rate. Say a tenant in a rent-stabilized apartment wants to move to Bermuda for a year, but doesn’t want to give up his sweet deal—he “sublets” his place to someone for that period of time, essentially charging them to hold his place while he’s away.

This conventional meaning of a sublessee confuses the term somewhat when it comes to co-op apartments, however. Because co-op shareholders technically, through a proprietary lease, own not the apartment itself, but shares of the cooperative, a tenant of the shareholder is considered a subtenant or the sublessee. If Jane is a shareholder residing in the Top Shelf Towers co-op building, and rents her apartment to Nick, Nick is a subtenant of Jane.

Because Top Shelf Towers is a co-op, Jane has a number of hurdles to jump in order to rent her apartment—Top Shelf Towers may not allow anyone to sublet their apartment at all. At first blush, the prohibition on renting out an apartment you own may seem downright un-American. Doesn’t the Constitution grant right of property? Yes, but a co-op’s governing documents make a different case.

“In a co-op, there is no right to sublet,” says Mitchell Posilkin, general counsel to the Rent Stabilization Association (RSA) and president of his co-op board. “There may be statutes that provide for subletting.”

Why Not?

In any case, there are a number of reasons why a co-op may choose to be choosy about subletting. “Co-op boards are often very protective of who is living in the building,” says Posilkin.

Indeed, if a co-op denies the application of, say, Madonna—as several have, according to the oft-repeated New York legend about celebrity turndowns—chances are it will be even stricter regarding subletting.

“Generally, co-ops like to have people living in the building who own the apartments,” explains Steven Wagner, of the law firm of Wagner Davis PC in Manhattan. “There is a belief—a well-founded one—that people take better care of their own property.”

Co-ops generally sell for less than comparable condos. The primary reason buyers choose the former is because of the higher rate of owner occupancy, and the degree of safety, cleanliness, and neighborliness that theoretically confers.

“There is a generally-held belief that no one cares about a co-op building as much as the people who own the units and have a general interest in upkeep, relations with neighbors, and so forth,” says Posilkin.

Another reason to kibosh subletting: the neighborhood feel. One of a co-op’s selling points is the sense of community that a cooperative actively cultivates.

“The co-op is a community,” explains attorney Kenneth R. Jacobs, a partner with the Yonkers-based law firm of Smith Buss & Jacobs LLP. “People tend to want neighbors who are there for the long term rather than people who are in and out. It enhances the sense of community.”

Indeed, the restriction on subletting, Jacobs says, “is consistent with the whole notion of approval rights over sales and leases—with the whole concept of cooperative living.”

That said, things are not always so cut-and-dried. There are plenty of wonderful tenants. There are also more than enough lousy owners. And most co-ops do allow subletting in some carefully regulated fashion. The idea is to protect the owners, not hurt them.

“Some boards allow subletting, but limit it so that the building can accommodate tenant shareholders who for whatever reason need to lease the apartment, but don’t want to sell or cannot sell,” explains Wagner.

For example, a shareholder may suddenly have to leave New York, but selling in this economy would mean taking a loss on the property. Subletting would potentially forestall financial ruin for that shareholder, and a compassionate board would likely entertain the idea of him or her bringing in a subtenant to avoid major money problems.

Subletting Issues

This business of rejecting sublessees or subtenants because they might not be a good fit for the building might make co-op boards seem fickle, if not mad with power. Although there are certainly a few Napoleons (or Catherine-the-Greats) on co-op boards, the fact is that there are other, more concrete reasons boards must limit the number of subtenants in their building.

“It has to do with lending,” Wagner says. “If a large number of apartments are not owner-occupied, some banks will look at that and not want to lend.”

The accepted ratio that banks look for is 3:1. If more than a quarter of the apartments in a co-op are sublets, banks will think twice about lending money or even refinancing—especially in a worsening economy.

“It affects the value of apartments if there are too many sublets,” Wagner continues. “It could prevent people from refinancing or selling because banks will be reluctant to make a loan.”

Complicating matters, sponsor apartments are included in the 25 percent tally the banks look at—they take up the first available spaces, sort of like legacies at Ivy League schools.

“If the sponsor still holds 25 percent of the units, and the building’s policy is to freely sublet, that may put the number over 25 percent,” notes Wagner.

In short, a liberal subletting policy could severely limit the financial options of not only the co-op, but of the individual shareholders of that co-op.

“Aside from policy issues, there are also individual issues,” says Wagner. In the case of sublets, co-ops and condos are very different. Co-ops are viewed by lenders as parts of a piece, whereas condos are considered the same as unattached houses.

“With a condo, you own it, so you’re not subletting,” says Wagner.

Still, many condo boards vie for greater control over their properties. They want to both have and eat the cake, in effect, desiring the ease of selling without approval and the ability to approve (or rather to reject) sales.

“In New York, condo regulations have been moving closer to those of co-ops,” says Jacobs.

Breakin’ the Law

All the rules in all the governing documents in all the co-op buildings in Manhattan will not stop some owners from subletting without board approval. Co-ops are not the most liquid of assets, and circumstances will make some owners take the risk.

What should a board do if it discovers an illegal subtenant in the building?

“As a practical matter, the key word is ‘discover,’” says Jacobs. “How do you discover that someone is illegally subletting?” The superintendent may be dispatched to play detective, knocking on the door to see just who is occupying the apartment.

“The person answering the door may introduce himself and say, ‘I’m the person’s cousin, or brother-in-law, and I’m staying here for a few months,’ and that may or may not be true,” says Jacobs.

Rather than call the cavalcade of attorneys right away, Jacobs suggests sending a letter first, notifying the occupant that there is suspicion of an illegal sublet.

“It gets things moving,” he says. “That will stimulate some action.”

Often enough, the letter is enough to spook the shareholder into terminating the agreement with the illegal subtenant.

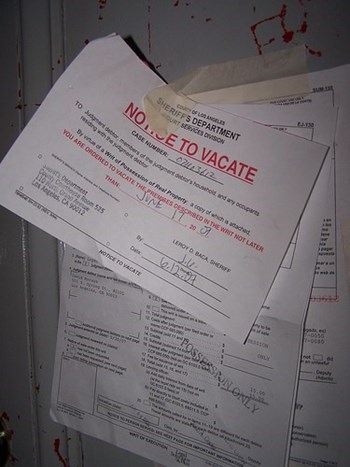

“We prefer to handle things without litigation,” Jacobs says. “Management companies would rather handle this forcefully, but outside of legal action.” If legal action is required, the first step is a notice of default, giving the shareholder ‘x’ number of days—as stipulated in the governing documents—to cure—in other words, to end the illegal activity.

“If they don’t cure,” Jacobs says, “they terminate the lease,” evicting both illegal tenant and shareholder, in a summary proceeding. “The shareholder will still have time to cure in the summary proceeding.”

With recidivist shareholders who wantonly sublet in violation of rules, there are other techniques, Wagner says, which culminate—in the worst-case scenario—with the guilty party being charged with contempt of court. But those scenarios are rare. “It happens from time to time, but not a lot,” says Jacobs. “There are more controls in a co-op. More people are watching.”

Greg Olear is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Comments

Leave a Comment