As an attorney and an apartment dweller, Michelle Freudenberger had seen it all and more when it comes to living with difficult residents.

“I lived next door to twin toddlers whose parents were both attorneys,” says Michelle, who in addition to being a real estate attorney is also a member of the national Association of Real Estate Women. “They took turns sleeping late and brought the kids to the kitchen early. Every morning, one child screeched at the crack of dawn.”

Wanting to keep peace, and understanding parenting challenges, she didn’t complain to the neighbors until one morning that was the last straw. She had been suffering with a bout of the flu and finally fell asleep around 4 a.m., only to be awoken once again by a screaming child. “I was banging on the walls out of desperation, but the father screamed back ‘get used to living in an apartment!’” she says.

Can't We All Just Get Along?

The reality is that while most co-op and condo buildings or HOAs will from time to time deal with this situation: either a noisy neighbor, a chronic complainer, or someone who habitually breaks house rules—Michelle and her other neighbors do not have to just ‘get used to it.’ Steps are typically outlined in the bylaws that residents, management and the board can take to effectively solve problems regarding objectionable tenants and turn a negative into a positive atmosphere.

Easier Said Than Done

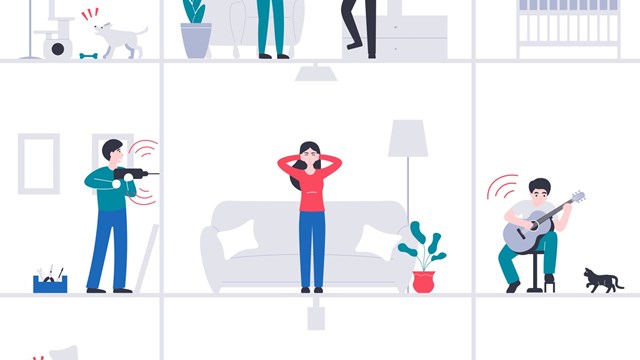

It’s human nature to complain but the top complaints from people living in close quarters at a co-op or a condo most often include noise, smoking and cooking smells, leaving belongings in shared hallways and vestibules, stealing laundry, and leaving exterior doors unlocked or ajar. Leaving a bike or a pile of toys outside your neighbor's door is a pretty clear-cut violation of their personal space, but because the concepts of 'noise' and 'disruption' are so subjective, dealing with them is somewhat trickier.

Judge William Huss, co-author of Homeowners Associations and You: The Ultimate Guide to Harmonious Community Living,(Sphinx Publishing; 2006), describes when a vocal tenant morphs into an ‘objectionable’ one. Simply put, “when the person who is complaining interferes with the normal atmosphere of the association’s activities.”

As many of us know, what is considered normal is in the eye (or ear) of the beholder, so dealing with conflict is not as easy as it sounds. Simple—but not always easy. There are many approaches to problem-solving with a difficult resident, depending on the nature of the problem. Most pros agree that solving neighbor-to-neighbor problems should generally start between the neighbors themselves.

“The first step is to try and have a conversation with them, not in the heat of the moment, but at a time when everyone has cooled off,” says Chicago-based attorney Jill Tanz, who is a professional mediator. She believes that calm and collected conversation is the first remedy to conflict. Residents can even turn to the management to act as an informal mediator, she says. In either case, the conversation should focus on the specific problem, triggers and solutions.

“I think what you want to look at is exactly what it is about the behavior that is causing the disruption. Is it the time? Is it the volume? Is it a pet? What is the problem? And then try and come up with like ways in which it can be resolved, so that those neighbors can live their life with as little disruption as possible,” Tanz explains. “For instance, if the problem is a dog, perhaps it can go to obedience training or be kept in a different part of the house.”

Conversations don’t always lead to solutions. One of the most famous examples of this is referred to in New York legal circles as “the Pullman case,” which was decided in 2003. This involved a shareholder at 40 West 67th Street, a bond trader named David Pullman. Shortly after he moved into his co-op, he allegedly began complaining loudly and often about his neighbors and certain members of the board, and is claimed to have altered his apartment without authorization. He filed noise complaints against an older couple living upstairs from him, sent multiple, strongly-worded letters to board members and management, and filed at least four lawsuits against various neighbors in the building.

The board countersued calling him an objectionable tenant and in 2000, voted to terminate Pullman’s lease. A decision in 2003 found in favor of the board by virtue of the business judgment rule. This landmark ruling now allows boards of directors to determine if a resident shareholder’s conduct is “objectionable” and can lead to termination of their lease.

Go to the Books

The bylaws and rules of your building or HOA can also reveal the correct timeline in addressing noise or routine disruptions in your condo or co-op. Managers stress that it’s important to not only follow the rules but pay attention to the timing so that the matter can be dealt with in a timely fashion. Turning to the bylaws can also help remove any personal baggage from the situation. “Try to find the impersonal rule that can be applied more objectively, and [the resolution] may be more peacefully accepted than just 'you're bothering me,' ” says Tanz.

Such was the case in Freudenberger’s situation, when her neighbors abruptly moved after being cited repeatedly for not complying with the condo's rule mandating that 80 percent of their floors be carpeted to muffle noise.

Stepping In

In cases where moving isn’t really an option for either party, yet one resident’s behavior is upsetting his or her neighbors’ ability to enjoy their residences peacefully, it’s the primary responsibility of the board and management to look into and resolve the problem once a unit owner has initiated a complaint. How the board acts will depend largely upon what’s laid out in the community’s bylaws.

When the board gets involved, it’s their duty to residents to act on their behalf and investigate the problem. Management pros recommend that boards and management conduct their own internal investigation to determine the depth and legitimacy of the problem.

Should this be ineffective, the board could also hold a public hearing in order to gain input on how to proceed with the case. “A board hearing to consider fines and other sanctions is a perfect vehicle for board and owner dialogue about the problems and offensive behavior.” Another option residents and management have is to hire an outside mediator to do the job. Although this is a lesser-known and utilized approach, it may prove beneficial, especially when resolution is far in sight.

“There are party mediators that can come in and help have a conversation and use skills that your typical property manager or your typical neighborhood service has not been trained to do and may be able to resolve the situation,” says Tanz. “There are community mediation services that provide free services in many areas or you can hire a commercial mediator who may very well be able to resolve the situation without you having to consider legal action.”

The Nuclear Option

Even seasoned professionals regard litigation as the option of last resort.

“The board and management have to be peacemakers,” says one manager. “If lawyer’s letters are involved, it’s going to cost the building money. If the case is won by the board, the shareholder or the unit owner has to pay the legal fees. If the case is not won, the building gets stuck with legal fees—and the building doesn’t want to do that.”

If your board has tried negotiating, mediating, and friendly-but-firm directives to get a problem resident to change their disruptive ways is to no avail, voting them out of the building community as happened in Pullman, may be the next—and final—step in solving the problem. And if an association board can show that they followed their own rules and acted according to their fiduciary and administrative duty to their community, chances are the courts will defer to the board's judgment on behalf of their residents.

In the end, dealing with a disruptive, unpleasant, problem resident is hard on everybody—both the disruptive resident’s neighbors, as well as the association board and building management. That said, neighbors, boards and management, who work together to resolve problems efficiently and effectively will find that most residents do not really want to cause problems—they just want to have their complaints heard and remedied.

Lisa Iannucci is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Chicagoland Cooperator. Editorial Assistant Maggie Puniewska contributed to this article.

Comments

Leave a Comment