Monthly charges, including common charges, emergency repairs, lawsuits, assessments, maintenance fees, dues and so forth, are a big part of owning a co-op or condo in New York City. When an owner is late, or misses monthly payments entirely, it affects the whole building and can adversely impact the entire community. There is less revenue that month, so savings may have to be raided. Property managers have to spend time better invested elsewhere dealing with the problem. Legal fees mount. And so on.

In the case of arrears, the difference between a co-op and a condo is vast, for reasons that are covered below. In short, co-ops are more insulated from potential financial harm than condos, whose ownership affiliations are tied to real property and personal mortgages.

What recourse do boards have when said payments are late or missed for months at a time? How does the process work? And how does it differ from co-op to condo? Let's take a look.

What is Arrears?

The word arrear is similar in sound and spelling to rear, as in one's hind quarters. And indeed, both words share the same Middle English root: arrere, meaning behind. To be in arrears—the word is always used colloquially in the plural—is a snazzy, legalese way of saying to be behind in one's payments.

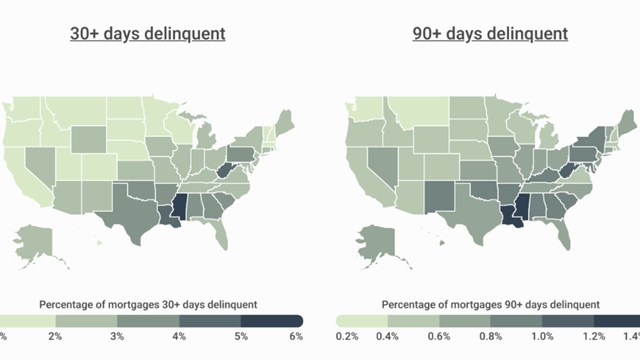

While no one presumably wishes to be in arrears, the vicissitudes of life, livelihood and the economy ensure that some delinquency is inevitable. Statistically, about two percent of units are in arrears at any given time. Why does this happen?

"They lost their job," says Steve Osman, chief executive officer of Metropolitan Pacific Properties in Astoria. "Or there's been a separation. Those are the most common reasons."

Late payments can be the result of laziness, inattention to detail, apathy, or, sometimes, an inefficient mail carrier. In some cases—usually with shareholders unfamiliar with local law—maintenance is withheld in protest, to "punish" the board for some shortcoming, real or perceived, just as tenants will withhold rent if, say, the heat hasn't been fixed for the entire month of February. Protest withholding doesn't last long.

"You can't self-escrow," says Osman. "It doesn't hold up in court."

More often that not, delinquent payments are the result of an intentional calculus. The mortgage gets paid before the maintenance, the thinking goes, because the consequences for withholding the former are more dire. While this is, on the surface, true, not paying the maintenance can, over time, have the exact same end result—especially in a cooperative building, where the retribution for missing payments can be swift and painful.

"We're not overly concerned with arrears [in cooperative buildings], because the co-op has the ability to control the transfer of shares," explains Marc Taub, CPA, and a partner with ERE, an accounting firm in Manhattan. "Condos are a lot more complicated."

Boards, of course, are not banks, who have armies of clerks on hand to pounce on a missed payment with alacrity. While they do ultimately have the power to foreclose on a property if the situation worsens, that eventuality is far from immediate, and comes with attendant legal costs. For the communities involved, collecting arrears can be a real pain in the you-know-what.

Timeline: Co-op

If you purchase a co-op apartment, you are not buying the real estate per se, but rather shares in the cooperative itself—enough shares to finance the apartment in which you live. Because you are bound by the proprietary lease, you are, in effect, both owner and tenant.

Because of this ownership structure, cooperatives enjoy more protection than do condos from financial havoc caused by shareholders being in arrears. Just as it is harder for missed payments to damage the co-op's bottom line for too long—cooperatives tend to have more money on hand for rainy days, and have the means to cut their losses more quickly—it is easier for co-op boards to foreclose upon delinquent properties.

"Co-ops can take back shares if a shareholder is in arrears," says Taub.

The process works like this: after the deadline has passed—30 or 60 days later, usually—the delinquent party receives an if-you-don't-pay-we'll-call-the-attorney letter.

"Typically, the managing agent sends a letter of admonition," says Stephen O'Connell, a partner at Hartman & Craven, a law firm in Manhattan. "They try to work it out outside of legal counsel. If there is no response, or an inadequate response—typically, there's no response—they give it to counsel."

"After 60 days, we put them on legal," says Osman, "unless there's some huge reason we shouldn't."

If the delinquent party pays up, the problem is solved. If not, and the shareholder has a mortgage, the bank gets involved. In this case, O'Connell says, mortgages are a blessing.

"Boards are leery about financing units," he says, "but the reality is, it's good to have a lender on these apartments."

For most properties, the mortgage holder is first on the foreclosure line. Not so with co-ops.

"The interest of the co-op is superior to that of the lender," O'Connell explains. If the shares are foreclosed upon by the board, "the lender is left with a note."

The positive application of this is as follows: rather than have the board foreclose on the shares—and lose the collateral—a bank will generally pony up the price of the maintenance fees, to preserve its own self-interest, while at the same time instituting foreclosure procedures of its own.

"With some cajoling," O'Connell says, a bank "will send a check for the missed payments, plus the attorney fees."

The process can be swift. In a few months, the shares can be foreclosed upon. And with a foreclosure in hand, a new owner can easily evict a delinquent ex-shareholder.

From a shareholder perspective, it's important to respond to those letters from the attorney. Osman recalls the sad case of a co-op owner in Brooklyn who was a recluse.

"He had no mortgage, he didn't answer the notices, he didn't show up in court, and his apartment was foreclosed on," he says.

While this is a rare occurrence, it isn't that rare. "I've seen people lose apartments for very stupid reasons," Osman says. "They don't answer the letter, they don't realize that it goes to the Supreme Court, it doesn't go to Housing Court, and they lose their apartment."

Timeline: Condo

The process for a condo is more complicated, because of the more conventional organizational structure. Because lenders have the first lien on condos, banks won't cover lost maintenance payments. If the delinquent party is also not paying his or her mortgage, this is not a problem—the bank will handle the foreclosure—but if the owner is paying their mortgage but not maintenance, it can take longer to straighten things out.

The laws are more sympathetic to owners who are losing their homes if the homes in question are condos. "People can be protected by bankruptcy," says Taub.

The first part of the equation—the letter-sending and the lawyer-calling—is the same for co-ops and condos. If the payments remain withheld, however, the process is different.

"You file a notice of lien," says O'Connell. "It's a filing. It's not a big deal. Now the owner can't sell without satisfying that. It preserves the rights of the condo."

If need be, the condo can foreclose on that lien.

Some Important Tips to Remember

Most owners want to pay their maintenance fees on time, and only miss them when there is financial hardship. In a sense, it's cut and dried—there's not much action the board can take. But here are some tips on handling arrears:

1. Don't allow arrears to get out of hand.

While it is not pleasant to take legal action against a neighbor, especially one who is in dire financial straits, the board must act in a professional manner.

"Boards have to be diligent," says Taub. "Act sooner, rather than later. Don't let people get too far in arrears."

Osman concurs. "You can't let people go on and on," he says.

2. Be consistent.

"There should be a consistent policy," says Osman. "Sixty days and they go on legal. Don't make deals individually."

Strict application of the rules has positive effects.

"It gets around the building," Osman says. "Don't get on arrears."

3. Be wary of side deals.

While there are situations when a board might choose to allow a delinquent shareholder to pay later—if, say, an owner has been sick but is going back to work and back on full salary—it is best to avoid favoritism.

"Boards shouldn't pick and choose who goes to legal and who doesn't," Osman says. "If you want to make a payment plan, do it in court, so we don't have a discrimination lawsuit."

Greg Olear is a freelance writer, editor and stay-at-home dad living in Highland, New York.

41 Comments

Leave a Comment