Any building in New York City taller than, say, five stories usually has an elevator—and often, new buildings of even three stories have one. If you live in a New York-area co-op or condo apartment building, chances are that you use an elevator every day.

Chances also are that you don’t give much thought to it, and when you look at the inspection report posted inside the elevator cab, you don’t spend much time analyzing it. Yet, elevators are essential to any mid-rise or high-rise apartment building. See how upset people are when their elevator is out of service for even a few hours!

In the Beginning

There have been elevator-like hoist devices throughout history, but in 1853, American inventor Elisha Otis invented a freight elevator equipped with a safety device to prevent the elevator from falling in case a cable broke. This increased the use of elevators. Other improvements followed, such as telephone communications between the operator and an “elevator supervisor” and signal-controlled elevators.

Before World War I, elevators were still fairly rare and confined by upscale apartment houses in neighborhoods like the Upper West Side, prestigious office buildings and fancy department stores. Many of the elevators of that period resembled luxurious, miniature drawing rooms, with small couches, wood paneling and uniformed operators. When New York City finally allowed the use of self-service elevators in apartment buildings in the 1920s, as opposed to those run by elevator operators, the number of apartment houses built with elevators grew dramatically. It wasn’t only luxury buildings anymore.

How They Work

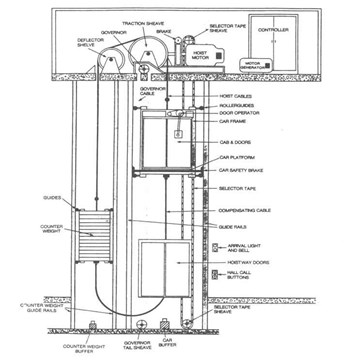

Today, there are basically two types of elevators in use—hydraulic and “rope-driven.” Chains or cables loop through the bottom of the counterweight to the underside of the car to help maintain balance by offsetting the weight of the suspension ropes. Guide rails that run the length of the shaft keep the car and counterweight from swaying or twisting during travel. Rollers are attached to the car and the counterweight to provide a smooth ride along the guide rails. An electric motor then turns the sheave. These motors are able to control speed and allow for the elevator's smooth acceleration and deceleration. Signal switches also stop the cab at each floor level.

In a hydraulic elevator, the car is lifted by a hydraulic-fluid driven piston mounted inside a cylinder. The cylinder—containing oil or a similar substance—is connected to a pumping system. The pump forces fluid into the tank leading to the cylinder; when enough fluid is collected, the piston is pushed upward, lifting the elevator car on its journey. When the car is signaled that it is approaching the correct floor, the control system will trigger the electric motor to gradually shut off the pump. To get the elevator to descend, the control system will send a signal to the valve operated electronically by a switch. When the valve is opened, the fluid flows out into a central reservoir, and the weight of the car and its cargo pushes down on the piston, driving more fluid out and causing the cab to move down.

Hydraulic elevators, says Brian Black, code and safety consultant for National Elevator Industry Inc., are fairly common nationwide, but are usually found in low-rise buildings of less than six stories. This is probably why they are outnumbered by traction elevators in the New York area. One well-known group of hydraulic elevators in New York can be found at Macy’s on the Fulton Mall in Brooklyn, formerly Abraham & Straus.

One of the most important changes in elevator maintenance during the past 20 or 30 years, says Michael Halpin, organizer for Local 1, International Union of Elevator Constructors, New York and New Jersey, is a factor that has increased safety—apprenticeship training for journeymen elevator repairers and maintainers.

“Journeymen now go through a four-year, state-certified apprenticeship program,” he says. “Before, there was education but there wasn’t a certified apprenticeship program.” Responsible contractors, he said, hire mechanics who go through this apprenticeship program.

(Local 1, by the way, is one of two elevator-based union locals active in the city—the other is Local 3, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.)

However, repair technicians aren't required to be licensed—an issue the New York City Council is working to address. Last April, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn proposed a bill that would require elevator technicians to be licensed to work in the city. The bill did not pass. Additionally, in 2011, Local 1 pushed for approval of Assembly bill A08359, requiring the licensing of persons engaged in the design, construction, operation, inspection, maintenance, alteration and repair of elevators. The bill went all the way to the Senate but did not pass. According to Michael Mottola of Manhattan-based Vertical Systems Analysis, Inc., the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) is now joining the fight in pushing for licensing requirements.

Computer-Aided Design

Another far-reaching change in the elevator industry, as in all industries, has been computerization. Whereas elevators 40 years ago or so were either controlled by relays or by an older type of solid-state controls, Black says, they are almost all computerized nowadays.

That said according to Black, “most elevators of any age are not obsolete. You can modernize systems, modernize old relay systems with a computer. Many elevators are being modernized on a regular basis. There’s no reason any elevator should be obsolete.”

Many of the most recent design improvements in elevator design are also safety-based, particularly in newer computerized systems. One example is a device called a rope gripper—if an elevator should move on its own (because of an error), the rope gripper will sense this and grip the cable, preventing it from moving further. And in general, in newer solid-state elevators, the car won’t move unless all the circuits are operating and all the doors are closed.

The DOB’s Elevator Division oversees the use and operation of the city’s elevators under the New York City Building Code and the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) codes, says Kelly Magee, press secretary for the Buildings Department.

“Virtually all codes are derivative of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers’ safety code for escalators and escalators,” adds Black. “Volunteers from the industry and building owners write the code every three years. New York City has quite a few modifications, but the framework is ASME A17.1 Safety Code for Elevators and Escalators.

For New York City guidelines, Magee points us to the city Building Code’s “Subchapter 18: Elevators and Conveyances,” which talks about general operations, signaling and switching equipment, alterations, and testing and inspection procedures.

It’s basically the responsibility of the building owner or manager (or, in the case of a condo or co-op, the board) to keep up to speed on these codes, new developments, and inspections. “Typically,” says Black, “the building owner will spell out that he’s expecting the elevator contractor to tell him [about these issues]. It’s typically written into the contract.”

What’s a good elevator maintenance inspection schedule—both as mandated by law and as recommended by industry experts?

According to Magee, the Department of Buildings performs one inspection of devices every 12 months. “There are also additional inspections every three to five years, depending on the device,” she says. The tests must be performed by an approved elevator inspection agency and witnessed by a second approved agency not affiliated with the one performing the inspection.

Halpin adds that a good schedule would also include monthly maintenance as well as annual inspections. “Maintenance is not in the city code, but it’s recommended,” he said. Mottola agrees, saying, “We think having a maintenance contract in effect which requires two hours monthly dedicated to maintenance is best.”

Speaking about the different types of tests, Halpin says, “There are annual tests and five-year tests. Annual tests don’t do a full load, but every five years, you do a test with a full load.” In addition, hydraulic elevators are subject to tests every three years.

According to Mottola, an elevator maintenance inspection can range from $500 to $1,600 per unit, depending on factors such as travel, building rise and equipment needed to conduct the service.

Testing, Testing?

Black further describes what tests can reveal. “They will make show if there are suddenly unintended car movements, whether the car is going too fast, of malfunctioning. The governor—a device that ensures that the elevator doesn’t overspeed—gets tested on a yearly basis. Devices that provide emergency power if there is a power outage would be tested once a year to be sure it kicks in properly. Door systems are tested once a year—you want to ensure your doors are opening and closing properly. You don’t want to close too quickly or strike a passenger.”

What happens if the inspection turns up a problem? If a Category 1 [annual inspection] test turns up a relatively minor problem, such as a sheave/bearing noise, the elevator contractor has 45 business days to correct the condition and must file a certificate of correction. In the event of a serious or hazardous condition, though, the elevator must be immediately removed from service, repaired, and restored to service only after it is retested and verified.

The DOB, by the way, has a schedule of filing fees and penalties that is posted online and found at http://www.nyc.gov/html/dob/html/development/elevator_fees.shtml. Filing fees are between $30 and $50, depending on the type of report (One-year, three- year or five-year). Fines for “failure to file” can reach as much as $5,000 per elevator.

While costs for inspections themselves vary, generally speaking, says Black, they increase with travel distance. This is not because the equipment is more expensive, but because of complexity. “Generally speaking, a 30-story building, you have 30 doors to inspect and maintain. With a three-story building, you only have three sets of doors.”

What are some of the most common problems affecting New York residential elevators? According to Halpin, door problems are the most frequent. “They could be caused by people, but not always. Doors work a lot. They are also critical to the operation of the elevator,” he said. Problems with doors can include door locks not making contact, the outer (hallway) elevator door not being in sync with the door on the actual elevator cab, and more. “Leveling” problems—or cars that don’t stop level with the landing—are also a common problem. “You don’t want a two-inch differential that people trip on,” Black said.

By developing a good relationship with an experienced contractor, addressing any problems promptly, and good care by your residents, your elevator should be operating on the up-and-up for many years to come.

Raanan Geberer is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator. Editorial Assistant Enjolie Esteve contributed to this article.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment