While recent reports point to signs of economic recovery, many co-ops and condos are still feeling the financial burden that has accumulated over the last few years due to increased operating costs, residents in arrears, defaults, and now repair costs in the wake of Superstorm Sandy.

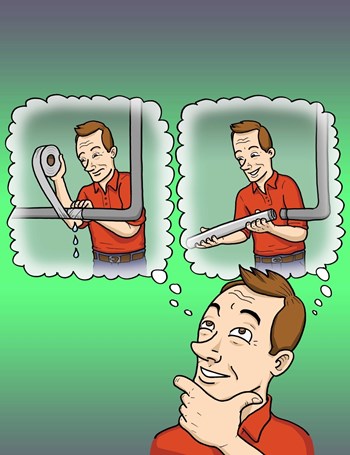

Many building administrators are looking for creative ways to save money and build up their bottom line, so it’s no surprise that many are taking a hard look at their maintenance and building improvement wish-lists—and making some tough decisions as they try to determine the projects they can afford to undertake, and which ones they need to put off until later.

Absolute Essentials

It’s safe to say that any physical issues that require attention must be addressed in a timely manner, regardless of how much it hurts. If an item is more cosmetic in nature, there may be greater latitude in deferring its maintenance—although most pros agree that poorly maintained aesthetic elements can quickly have a negative impact on the perceived value of a building. Other than that, deferred maintenance on a building’s structural or mechanical elements will inevitably result in higher costs the longer they are ignored.

According to Doug Weinstein, director of operations and compliance with AKAM Associates, Inc., a property management firm in Manhattan, the following maintenance projects must be performed annually in order to ensure the proper operation of the building: Burner overhaul before the heating season, roof tank cleaning, elevator inspection, backflow preventer inspections, fire extinguisher inspection and re-charging, sprinkler system inspection, and proper commissioning of the air conditioning system for cooling season.

“Signs and symptoms of an impending maintenance crisis that boards and managers should never ignore or put off include cracks in exterior walls, roof and roof tank leaks, excessive chimney exhaust, elevators that don’t level or otherwise operate properly and heaving sidewalk flags,” Weinstein says. “These problems must be addressed immediately in order to avoid major problems and repair or replacement expenses.”

Debra Bechtel, associate clinical professor at Brooklyn Law School, who serves as the board president in her co-op, says that it’s not always easy to decide what can and can’t be put off because these are so many gray areas.

“Roof leaks, for example, shouldn’t be ignored but sometimes minimal patching may be done with further work postponed until the next rain or after in order to assess the seriousness of the problem,” she says. “A new roof is such an expensive project that many building managers recommend this patch, wait and see type of approach.”

The cost of a new roof will increase somewhat over time, but if a board can hold off spending that $200,000 or whatever it is for five to eight years, it might be worthwhile.

“Waiting has another downside, though, in addition to the risk that the upgrade might cost more; that is, the situation might become more of a crisis which won’t leave the board as much time to explore various options,” Bechtel says. “It’s always better to plan for a roof upgrade than to be required to do it very quickly.”

One thing that is necessary are façade inspections, which have to be done pursuant to Local Law 11 on a five-year reporting cycle with necessary work completed according to an engineering report ordered by the building owner.

“There might be caulking and other façade work that could be done during one Local Law 11 cycle but isn’t required,” Bechtel says. “The board might choose to take the risk of some small leaks and wait on the work until an engineer says it’s actually required.”

On Hold

This reshuffling of priorities may be unavoidable given the state of the economy, but the process raises some definite questions about liability, long-term planning, and how boards and managers can make wise decisions in tough times.

Greg Cohen, president of Impact Real Estate Management, Inc., with offices in Queens, Manhattan, Long Island and Westchester, understands that with the economy the way it has been, you need to squeeze whatever you can out of your building and that necessitates the need for putting things off left and right.

“With roofs, what you’re really seeing is more patching work so you’re not seeing what really needs to be done,” he says. “I can go in and tell them the roof is past its life span and there are roof leaks, but what boards are saying is that instead of spending money on getting a new roof, let’s patch it and get another 3 or 4 years out of it.”

Beautifying landscapes is another project that condos and co-ops are putting off, as are things like installing or upgrading roof decks and other amenities.

“Some things in terms of major capital projects are being put on hold, while some are being phased in, rather than doing it all at once,” says Roberta Axelrod, director of co-op and condo sales and conversions for Time Equities, Inc., a Manhattan based real estate company. Axelrod sits on a dozen condo and co-op boards across the city. “Lots of cosmetic work is being postponed.”

Oh, Sandy

It’s always good to have a maintenance plan and strategy in place, but sometimes something like Superstorm Sandy comes along and serves to aggravate existing repair and maintenance issues and reveal latent or other defective conditions that perhaps did not seem critical but now must be addressed.

“Co-ops and condos must now consider making repairs and changes to maintenance based on what problems arose from the storm,” says Patricia Kantor, a partner with the real estate law firm of Edwards Wildman Palmer LLP.

Some examples experienced by her clients included windows that blew open because they couldn’t withstand the high winds, roof drains that were blocked, clogged and/or hadn’t been cleaned properly and couldn’t adequately handle the water and debris that accumulated, and landscaping that was uprooted.

“None of these items may have previously been a priority but now that the boards have notice of the defective conditions, they may have to be addressed more promptly, particularly those that could result in further danger or damage to people and/or property,” Kantor says. “For example, landscaping may not be a priority for buildings struggling financially, but if there are old trees or limbs that were weakened by Sandy, they must be dealt with promptly.”

Legal Issues

The board of directors is held to a reasonable business judgment standard, which means that courts will not substitute their sense of what a good decision would have been for the board’s decision.

Let’s say a board patches a roof and then $40,000 of damages occur which leads to a shareholder assessment, shareholders might complain and say that they board should not have waited. However, if the board has contractors, the manager and maybe even an architect who told them that patching was worth a try, how will the shareholder show that the approach wasn’t a reasonable choice?

“The court will not re-assess all the facts and circumstances. Instead, a shareholder challenging a board decision has the burden of showing that the decision was not reasonable,” Bechtel says. “This makes challenges difficult but not impossible.”

Cohen cites an example of a building that had leaks all over the place including going into a shareholder’s unit. He recommended to the board that they hire an engineer and do a set of specs, and the job would cost $200,000. If the board continues their waiting game, the shareholder might turn around and sue them for negligence.

Making a Plan

Every board should be able to rely on their management company to direct their building’s maintenance needs and schedule satisfactorily.

“A thorough preventive maintenance program is the best way to ensure that a building will not suffer premature failure of its major systems,” Weinstein says. “When we go into a building, one of the first things we do is review all warranties and service contracts. We also perform a full-building audit on all structural and mechanical systems in order to establish a baseline, identify remaining useful life, and anticipate future maintenance, repair, and replacement costs.”

These activities are crucial to the annual budgeting process and ongoing capital planning process of a building.

It’s always a good idea to make a list of those things that need to be done and those that can wait, with a proposed schedule of when you plan to do them.

“Boards should consult with engineers, architects and their property managers to develop a thoughtful 2-to-5 year physical plant/maintenance and repair plan,” Kantor says. “Priority should always be for conditions that affect or could affect the health, safety and well-being of building occupants and the public.”

Once a plan is made, it should be adhered to and not changed to constantly push things back.

“Our policy is that mechanical and structural items that have been scheduled for regular maintenance in order to ensure the proper operation of a building should never be deferred,” Weinstein says. “We advise our client boards that a dollar spent now on maintenance and repairs as necessary will save a building five times that compared to the cost of performing major repairs or replacements.”

The best thing to do is listen to the professionals the building hired in the first place. “If you have a strong managing agent and a strong attorney, they should be able to give advice on how to handle things,” Cohen says. “I always tell my boards that those that listen to us are the ones that get through the problems. Those that think they are smarter than the managing agent are the ones that get into trouble. You are hiring these people to give you professional advice and you should listen to it.”

Keith Loria is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment