As an attorney and an apartment dweller, Michelle Freudenberger has seen it all when it comes to living with difficult residents.

“I lived next door to twin toddlers whose parents were both attorneys,” says Freudenberger, principal attorney for the Law Offices of Michelle Freudenberger in Manhattan and a member of the Association of Real Estate Women (AREW). “They took turns sleeping late and brought the kids to the kitchen early. Every morning, one child screeched at the crack of dawn.”

Wanting to keep peace, and understanding parenting challenges, she didn’t complain to the neighbors until one morning when she had been suffering with a bout of the flu and finally fell asleep around 4 a.m., only to be awoken once again by a screaming child.

“I was banging on the walls out of desperation, but the father screamed back ‘get used to living in an apartment!’ ” says Freudenberger.

Can’t we all just get along?

The reality is that while most cooperative and condominiums will, at one time or another, have difficult residents—a noisy neighbor, a complaining shareholder, or perhaps a more difficult tenant who habitually breaks the house rules—Freudenberger and others do not have to ‘get used to it.’ There are several steps that should be outlined in the board’s or association’s bylaws, that a resident, management and the board can take to effectively solve the problems of objectionable tenants and ultimately create a positive neighborhood atmosphere throughout the building community.

More than Just Noise

Neighbors can complain about a host of things, but some of the most common complaints from shareholder to shareholder include: excessive noise; smoking; leaving belongings out; stealing laundry; and not locking doors after exiting or entering. However, being a problem tenant is not limited to just troubles with Mr. and Mrs. Jones next door—resident shareholders or unit owners can also cause disruptions among board members.

“A board member shouldn’t ever feel threatened by a shareholder,” says Freudenberger. “They also shouldn’t make calls late at night to discuss personal business and not more than once a week to give them time.”

According to Judge William Huss, co-author of Homeowners Associations and You: The Ultimate Guide to Harmonious Community Living, (Sphinx Publishing; 2006), a vocal tenant morphs into an ‘objectionable’ tenant “[When] the person who is complaining interferes with the normal atmosphere of the association’s activities.”

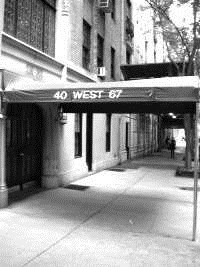

Probably one of the most infamous examples of this is the recent case of 40 West 67th Street v. Pullman.

In a nutshell, Pullman’s troubles began when he began to accuse his upstairs neighbors of a litany of house infractions, including excessive television noise and the creation of what he called ‘toxic’ odors from a bookbinding business he claimed his neighbors were running out of their apartment. Pullman proceeded to complain to the board multiple times and, as a result, the board conducted its own internal investigation. The situation began to turn weird when the board found that the accused neighbors didn’t even own a television set—and had no equipment capable of producing any of the odors that Pullman complained of. Not satisfied with the results of the board’s investigation, Pullman initiated four lawsuits against the co-op, and began distributing flyers and circulating spurious rumors regarding the private behavior of certain board members. The excessive and unnecessary demand the lawsuits placed on the board’s time, energy and resources, combined with the personal attacks led the board to convene a special meeting and make the decision to terminate Pullman’s lease.

The case went to court, and not only was Pullman’s lease terminated, but the case was a precedent setter. Thanks to that decision, co-op boards are now no longer required to prove that an objectionable tenant’s behavior is objectionable solely as defined by law. If their governing documents give them the power to evict a shareholder or to call for an eviction vote from the rest of the building residents, the courts will not second-guess them. The court found that the determination of the board and shareholders constituted enough of proof that Pullman acted objectionably and he was consequently evicted.

According to Deborah Gordon, director of operations at Kaled Management Corporation in Westbury, although the Pullman case is considered an extreme one and Pullman himself did have the right to complain about conditions in the building he found unacceptable, “The case shows that the shareholder was harassing the entire building, not necessarily just the board.”

Solving the Problem

There are many approaches to problem solving, depending on the nature of the problem. Solving neighbor-to-neighbor problems should simply start between the neighbors themselves.

“First, you should try to straighten out everything in a friendly manner,” says Freudenberger, who suggests—in a situation such as hers—knocking on the neighbor’s door and try to discuss the problem in a calm, civil manner. “But if that doesn’t work, the shareholder should start documenting the problem and then send a certified letter to the board and management.”

Freudenberger’s situation ended when her neighbors abruptly moved after being cited for not complying with the 80 percent carpeting rule, which might have softened the noise.

In cases where moving isn’t really an option for either party, yet one resident’s behavior is upsetting his or her neighbors’ ability to enjoy their apartments peacefully, it’s the primary responsibility of the board and management to look into and resolve the problem once a shareholder has initiated a complaint. How exactly the board acts will depend largely on what’s laid out in the community’s bylaws.

“When the board gets involved, it’s their duty to shareholders to act on their behalf and investigate the problem,” says Gordon, who recommends that boards and management conduct their own internal investigations to determine the depth and legitimacy of the problem. The last resort should be litigation.

“The board and management have to be peacemakers,” says Gordon. “If lawyer’s letters are involved, it’s going to cost the building money. If the board wins the case, the shareholder has to pay the legal fees. If the case is not won, the building gets stuck with legal fees—and the building doesn’t want to do that.”

Iris Shorin, a real estate attorney and an associate with DJK Residential in Manhattan lives what she calls a “traditional, non-litigious” building and says this type of building can exist. “Neighbors may sue neighbors, but we’re not a litigious board,” she explains. “We know how much litigation costs, and we will try to settle with the resident no matter how long it takes.”

In some associations, mediation is another problem-solving possibility. To minimize potential problems neighbor-to-neighbor or shareholder-to-board, Huss makes several recommendations, including:

• Give everyone who wants to speak a chance: “Every meeting should have a certain time when members can speak out about certain problems,” he says. “The people have to feel they are having that opportunity.”

• Avoid special treatment for certain members—“Some board members are tempted to ask for all kinds of special privileges, and when anyone is given special treatment it creates animosity and creates litigation.”

The Last Straw

If your board has tried negotiating, mediating, and friendly-but-firm directives to get a problem resident to change their disruptive ways to no avail, voting them out of the building may be the next, and final, step in solving the problem. “Ejecting a tenant is the most serious thing a board can do,” says Gil Feder, a partner with the Manhattan-based law firm of Reed Smith. “In the court system, the courts will defer to what the board did—as long as the board followed the rules.”

Those rules, explains Feder, include sending a tenant a notice of the board’s intention to evict them and, like Huss explained, giving them that critical opportunity to be heard.

“The notice must be detailed, telling the shareholder what they’ve done,” says Feder. “The letter should outline how long they have to fix the problem; sometimes, if it’s one incident, they’ll say don’t do it again.”

A tenant can overturn the eviction decision if, according to Feder, the board acted outside the scope of authority, if it didn’t follow the provisions in the proprietary lease, or if it acted in bad faith. “But it’s rare to find a court that won’t go with a board’s final decision,” says Feder.

In the end, dealing with a disruptive, unpleasant, problem resident is hard on everybody—both the disruptive resident’s neighbors, as well as the board and building management. That said, neighbors, boards and management who work together to resolve problems efficiently and effectively will find that the residents do not really want to cause problems—they just want to have their complaints heard and fixed.

Lisa Iannucci is a freelance writer living in Poughkeepsie, New York and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

24 Comments

Leave a Comment