Thirty-eight of the 400 individuals on Forbes magazine's list of the richest Americans—almost ten percent—call New York City home. All thirty-eight are billionaires. Some of them, like Ralph Lauren and Donald Trump, are household names. Two of them are Rockefellers. One of them, Michael R. Bloomberg, is the mayor.

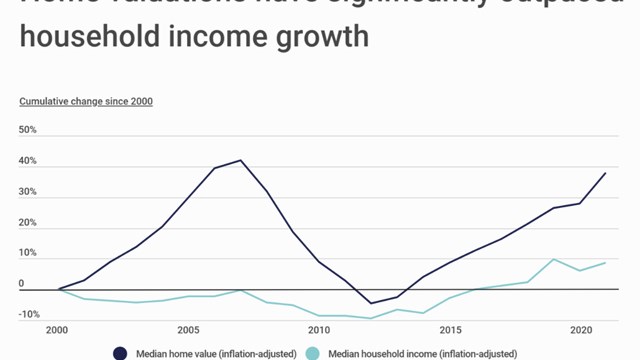

The point is, big money is so integral to the Big Apple that when the appraisal firm Miller Samuel reports that the average apartment in Manhattan is selling for $1.22 million, New Yorkers respond with a shrug.

But let's put that in perspective. According to the National Association of Realtors (NAR), the average home price for the entire United States is $220,000, give or take. That means—ready for this?—the average apartment in Manhattan costs a million dollars more than the average U.S. home.

Let's break it down further. Most co-ops require a minimum of twenty percent down (the super-exclusive buildings on Fifth and Park Avenues and Central Park West often require a full cash purchase, but that's a different article entirely). Then there are the closing costs. Mortgage taxes, legal fees—there can be as many as five attorneys at a closing: the buyer's, the seller's, the co-op's, and the two banks'—appraisal costs, mortgage taxes, transfer fees, flip taxes, and, for all apartments sold at a million bucks and higher, the so-called "mansion tax" of one percent. (The six percent broker's fee, generally evenly divided between the listing and selling agencies, is picked up by the seller). When all is said and done, you need about $220,000 up-front in liquid cash to buy a million-dollar apartment. For that amount of money, you could buy a house outright most places in the country.

Everybody Else

All that said, most New Yorkers are not Rupert Murdoch, Carl Icahn, or David H. Koch (numbers 32, 24 and 19, respectively, on the Forbes list and the three richest men in Gotham). In fact, according to Bloomberg News, the average yearly income in Manhattan is a "mere" $73,000. So who's buying these seven-figure apartments, and how are they doing it? Is now a good time to buy? To sell? To move to Pittsburgh? And what does the future hold for New York real estate?

According to the experts, many first-time buyers are young professional couples who don't make enough to buy on their own, but are able to, once their individual bank accounts become joint checking accounts. A $4,300 mortgage payment may become less prohibitive when two incomes are involved.

"You see young couples who are just getting married, or just having babies and need more space," says Michele Kleier, president of the Gumley Haft Kleier real estate brokerage, speaking about the profile of many of her clients.

Rob Anzalone, the chairman and CEO of Fenwick-Keats Goodstein Realty, says that buyers of million-dollar apartments comprise a "mixed bag."

"A majority are 30-something, or in the 30-to-40 range, and are professionals," he says. "The banking industry probably leads the pack. Corporate professionals, followed by attorneys, doctors, and young executives."

The real estate market, Kleier says, is closely tied to bonuses, which in 2006 reached record highs. First-time buyers tend to jump into the market after a big bonus—or, paradoxically, before not getting one. This contributed to the relatively busy fourth quarter last year. The top five financial firms, for example, awarded more than $36 billion in bonuses to its top executives on Wall Street. And the average employee of those firms will easily top six figures—earning between $300,000 to $600,000 annually.

"Everything is selling," explains Kleier, whose high-profile clientele have included the likes of Billy Joel, Neil Diamond, Richard Gere, Katie Couric, John Travolta, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino, to name a few. "It started in November, when people who weren't getting bonuses starting looking immediately, to beat the rush."

A case in point: among the big-ticket sales: the $27.5 million paid by New York Stock Exchange Chief Executive John Thain for a two-bedroom duplex apartment at 740 Park Avenue, one of the city's most storied addresses. Formerly home to Rockefellers, Vanderbilts and Chryslers, the building's current residents include cosmetics executive Ronald Lauder and Blackstone Group chief Stephen A. Schwarzman.

"When these guys learn what their bonuses are, we are among the first people they call," Pamela Liebman, president and chief executive officer of the Corcoran Group, a residential brokerage, told The New York Times-owned International Herald Tribune. "They call their mothers and then their real estate brokers."

The investment bankers tend to be interested in buying a luxury apartment in Manhattan or a second or third residence elsewhere. And the bonus bonanza is not limited to the top executives of Wall Street brokerage houses. "Even the junior guys want to spend their bonuses on residential real estate," Liebman says.

Brokers also point out that interest rates have gone up slightly but remain low by historical standards. The Federal Reserve has held steady for now, but that may not last. All of this contributes to the busy market.

Buy When You're Ready

Michael and Lahnie Strange, a married couple in their thirties, bought their first apartment this past January.

"We were tired of renting," he says. "We did some math, put together some fairly comprehensive spreadsheets, and saw that once you factored in rent and other expenses, we would be better off buying."

They had wanted to buy when they were first married, but had to wait until Lahnie's business school—she has an MBA from Columbia—was paid off.

"We started looking back in 2000 and 2001," he says, "but we stopped because it wasn't right financially."

Both were recently promoted, he to director of client management at a financial services corporation, she to director of North American marketing at a cosmetics company, which hastened their decision to buy when they did. They don't regret their decision one bit.

"Based on comparable appraisals," he says, "I think we already got a good deal."

Waiting turned out to be the right move for the Stranges, but it hasn't worked out for everyone. Kleier says that some buyers who decided to wait till the bubble burst have leapt back into the market, because the expected market correction never came. "There is no bubble," she says.

In the meantime, prices have continued to soar, with some buyers being forced to settle for smaller apartments. "What used to cost six million now costs over seven," she says.

Six million dollars can't buy you the right apartment? Only in New York!

With prices rising inexorably, the best time to buy is as soon as possible, right?

"People always ask me when is a good time to buy," Anzalone says, "and my answer is always the same: when you're ready. When you're financially ready and psychologically ready and properly motivated, you should buy."

Is there any reason you shouldn't buy, if you have the means?

"If you're not certain where you'll be in a year," he says. "If, let's say, you're getting transferred and have to sell after six months, you're vulnerable to a loss, even in a good market. As long as you have a three-year plan, that's sound."

The Investment Option

A number of million-dollar apartments, especially new condominium constructions, are scooped up as investments. Some owners live overseas, and others are stateside.

"Some buyers are just out of college and their parents are doing it," Kleier says, "especially if they have children down the road."

Indeed, in this age of Enron and Global Crossing, a Manhattan apartment is perceived as a safe investment, as secure as the bedrock on which the skyscrapers are anchored.

"It's a safe, solid, sound investment," Anzalone says, "but it's also enjoyable."

"New York has more of a mass appeal now," he points out. "It's no longer just sophisticated people. It's become more family friendly, and has more of a wider appeal. It's become more of a destination."

While many of investors remain foreign - "There's a strong Asian market," says Anzalone. "The Korean market is very high."—in the last few years, Anzalone has seen a rise in investors from the other forty-nine states.

"People are thinking of retiring in New York," he says. "You see more people doing tax exchanges, selling homes elsewhere and buying apartments in New York. You see couples who left the city to have kids who move back after their kids are grown."

Apartment as Investment

With so much money from so many different people tied up in so many apartments, and so many people wanting to crash the party, conventional wisdom holds that, absent unforeseen and unforeseeable disaster, a New York apartment is a great investment.

"I feel very good about it," Strange says of his decision to buy. He likens the real estate market to the stock market. "When the stock market crashes, all your fringe stocks will be affected more—your stronger neighborhoods, like your blue chips, won't take as much of a hit."

Kleier sees no end in sight to the rising prices.

"The buyers today are very sophisticated," she says. "If there's a hole in the ground, if the location is right, buyers are already out there."

The reason, she says, is that there is a shortage of quality apartments, especially for larger families. "There's a lack of good product," she explains. And a lack of supply, as we all know from Economics 101, tends to yield an increase in demand.

Anzalone, while bullish on the future of New York real estate, doesn't see things quite as rosily.

"The buyer is in a comfortable position," he says. "They're not waiting in lines to see new construction. They can take more time to make their decisions. I wouldn't say that it's a buyer's market, but it's more comfortable."

He has also seen signs that things are beginning to slow down, if slightly.

"There's more cocktail parties," he says. "When they start to turn up the cocktail parties, you know they want us there. You know they're sweating a bit."

Overall, however, Anzalone holds with the conventional wisdom.

"Put it this way," he says. "I know only a few people who have regretted buying—but quite a lot who have regretted not buying."

Greg Olear is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

9 Comments

Leave a Comment