Thirty years ago, Cats won the Tony Award for best musical, setting it off to secure its place as the second longest running Broadway musical in history. New York City streets were filled with women in torn sweatshirts and leg warmers inspired by everyone’s favorite steel-welding, break dancing ballerina portrayed by Jennifer Beals in Flashdance.

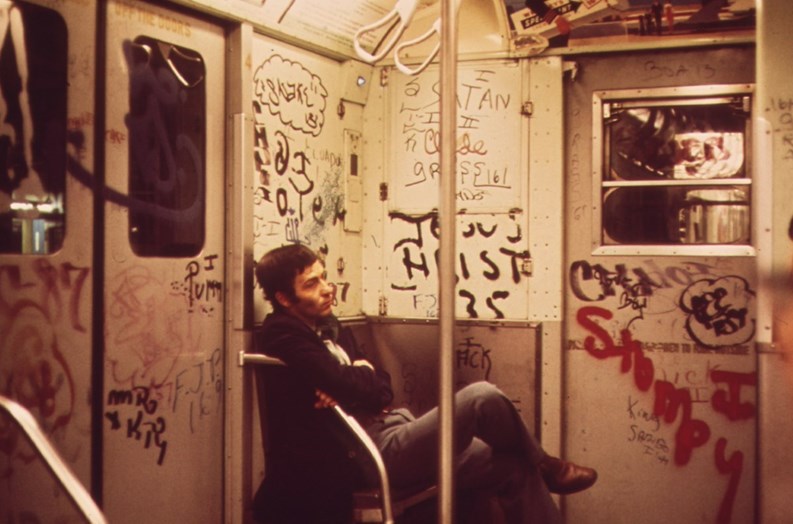

The city subways were rolling art galleries with graffiti covering nearly every square inch of space inside and outside of the cars. MTV debuted the first music video, “Video Killed the Radio Star” by The Buggles and millions watched Michael Jackson perform the moonwalk for the first time on live television. And a real slice of New York pizza was one dollar (although you can still get a slice for a buck, it’s not the same.) George Lucas released Return of the Jedi, the final installation of the first Star Wars trilogy.

In the 1980s no one had any idea what the city would look like in thirty years. Given the way the city was, many envisioned a 2013 New York to be an apocalyptic wasteland,—the future of New York City seemed like it would more resemble John Carpenter’s vision from Escape from New York than it would Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.At the time, homelessness was endemic; entire neighborhoods resembled war-ravaged bombed-out cities; the AIDS epidemic was beginning to decimate the community; and drug abuse was a pandemic. Fortunately the future has been kind and after 30 years, New York has gone from the place to avoid to the place to live once again. This month we look at some of the unsung legal and regulatory changes that greatly contributed to New York City progress.

Mean Streets to Clean Streets

Perhaps the most iconic memory many of us who lived through the 1980's remembers is that of Bernhard Goetz, the so-called “subway vigilante” surrendering to police in Concord, Massachusetts a week after he shot four young men on a New York City subway believing they were about to mug him. Goetz became a media superstar leaving the city deeply divided and widening the city's already simmering racial tensions. This incident even today reflects how many New Yorkers view the 1980s.

Sure, the Disneyfication of Times Square gets most of the anecdotal praise (or blame) for the transformation of New York. But from a residential standpoint, two smaller, much less publicized factors may have had an equal—if not larger—long-term impact on life in the Big Apple: the “Pooper Scooper Law” and the “Bottle Bill.”

The law commonly referred to as the "pooper-scooper law” is actually the city's Canine Waste Law, which forced New Yorkers to clean up after their dogs, and first went into effect in August 1978. In the 1980’s, The Sanitation Department (DSNY) enforcement unit carefully trained officers put them out on the streets with the mission of spotting and fining violators. "If you've ever stepped in dog doo, you know how important it is to enforce the canine waste law," said former Mayor Ed Koch in an anniversary report in 2004. “New Yorkers overwhelmingly do their duty and self-enforce.” By 2008, however, New Yorkers were not self-enforcing enough, and the pet waste fine was raised from its longstanding $100 to $250. To be sure, people still flout the law and leave pet mess on the sidewalks, but thanks to the Canine Waste Law, walking down the street is a little less like an unhygienic obstacle course than it was three decades ago.

The other unsung hero is the New York State Returnable Container Law also known as the “Bottle Bill.” First implemented in July of 1983, the purpose of the law was to “reduce litter, ease burden on solid waste facilities and encourage recycling activity.” Under the Bottle Bill, the metal, glass, paper, or plastic containers of everything from soda to wine coolers required a deposit, which was returnable for five cents at retail stores and redemption centers throughout the five boroughs. More than just giving the homeless something to do, the Bottle Bill had a slow but measurable positive effect on the amount of garbage cluttering the city’s streets. In 2009, it was established that 80 percent of the unredeemed deposits would go to the state’s General Fund and 20 percent retained by distributors, adding to some of the city’s increasing need for resources at the time.

According to New York’s Public Interest Research Group’s (NYPIRG) Laura Haight, in the years after the implementation, the state of New York collected over $120 million in unclaimed deposits from the expanded bottle bill, placing it on target with the state’s budget projection of $118 million. These two laws in conjunction with later stricter laws on recycling in 1989 and 2010 have contributed greatly to cleaning up of the city’s streets—and in turn, its reputation.

A Tree Doesn’t Just Grow in Brooklyn Anymore

There was a joke back in the 1980s about Central Park, the comedian related that, “It's springtime here in New York and my, isn't it pretty, I walked through the park today...the tree was blooming and the bird was singing.”

Since then much has changed, the Central Park Conservancy has successfully brought the park back from ruination. Along with these preservation projects, community gardens have grown all around the city turning vacant lots into neighborhood gathering places, the Hudson River Walk has transformed rotting piers into parks and playgrounds, and thanks to environmental concerns more and more roof gardens are springing to life. There are many more programs endeavoring to bring natural beauty to the city.

In April 2007, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg introduced his 127-point plan for greening the Big Apple, known as PlaNYC. The plan’s mission was to create and maintain a more environmentally-friendly New York City, as well as improve housing and transportation, and by and large it has been succeeding. MillionTreesNYC, one of these 127 steps to a better city, is his program with the ambitious goal of planting 1,000,000 new trees throughout the city by 2017.

At its inception, it was estimated that the organization would plant 220,000 street trees, 380,000 trees in parks and other public areas, and 400,000 on private and community organization property. Homeowners were factored into the last 40 percent and given the option to request a tree be planted on their property through the MillionTreesNYC website (www.million treesnyc.org.) To date, 645,804 trees have been planted throughout the five boroughs.

Trees are nature’s natural filters; they absorb toxins and release fresh oxygen into the air. In a densely-populated city that relies heavily on fuel emitting vehicles for transportation, trees are important in keeping the air clean and promoting healthy living conditions. So in addition to cleaner streets, these trees contribute to cleaner air. And this initiative adds favorably to the value of the co-op and condo buildings throughout the city by helping to improve the health for all New York residents.

More Environmentally Friendly

In the 1980s “going green” meant no more than jogging over to Central Park (usually with a can of mace stowed close at hand). Today, along with the marked decrease in crime, the city has greatly increased its investment and interest in green technologies and sustainability focused initiatives.

Often, when building boards or shareholders think about “going green” they become paralyzed by images of bamboo flooring, hemp drapes, or solar panels on the roof. Many are still left feeling that because one lives in a condo or other multifamily building, green upgrades are difficult and costly to do. Fortunately, the truth is that there are plenty of things condos and condo owners can do—and the New York City of today offers an array of ways to improve the energy efficiency and durability of a community’s property.

According to the experts such as David Unger, CEO of U.S. Energy Group, based in Fresh Meadows, “When you really start looking at what it takes to go green, you recognize that it's all about cutting energy use. If I can use less oil, I'm going green by virtue of the fact that I'm not dependent on oil.”

In April 2011, Mayor Bloomberg and Environmental Protection Commissioner Cas Holloway tried to move the city forward by announcing a PlaNYC update. The phase-out of the dirtiest fuel, No. 6 heating oil has begun, as the DEP is no longer issuing permits for that grade, and will soon stop issuing permits for No. 4 heating oil as well. Boilers must either use No. 2 heating oil, biodiesel, natural gas or steam, instead.

The full phase-out of No. 6 oil is expected by mid-2015. By 2030, all buildings must have converted to one of the cleaner fuels. Mayor Bloomberg stated, “To clean the air New Yorkers breathe we are going to gradually phase out the dirtiest types of heating oil, by changing the type of oil we use, we will reduce pollutants and spend less money on maintaining and operating our heating systems. This helps our PlaNYC effort to fight asthma, prolong lives, lengthen life spans and improve quality-of-life.”

Prices Went Up...Up...Up!

According to Jonathan Miller, president of Miller Samuel Real Estate Appraisers, which was started in 1986, “In the ‘80s, which is when I started appraising, the ‘80s housing market was defined by rental to co-op conversion, so we had a tremendous volume of co-ops traded out of the rental housing stock, and we had a tremendous amount of new condos being constructed largely for investors. The units that came into the housing stock in the ‘80s tended to be smaller-- studios, one bedroom, some two bedrooms.”

Miller points out that these conversions significantly reduced a sizable portion of the rental stock, which is why in today's market we're not seeing much conversion activity right now.

Another key housing change or trend over the last 30 years happened during the 1990s when, according to Miller, “We had the establishment of a new housing type, which were lofts. Lofts have been around a long time but they became an alternative to Upper East and Upper West Side large-size apartments. You were seeing people from Park Avenue move to Soho or Tribeca. Luxury amenities were part of this and to this day this trend continues.”

According to The New York Times'Susan Stellin, “The gap has been narrowing in recent decades.” Citing data gathered by Noah Rosenblatt, the founder of the real estate analytics site UrbanDigs, Stellin reports the vast majority of the apartments for sale in areas such as Battery Park City are condominiums. However, in areas such as the Upper East Side, there were 942 co-ops on the market in early October and 370 condos.

“The current development craze, started in the 1990s but continues to this day,” says Lawrence F. Kramer, vice president of V. Paulius & Associates, a real estate development firm that has built numerous projects in New York. “New York City continues to be in a prolific phase of development. The 2008 housing crisis slowed things down, but now development is in high gear once again. And this development craze is almost exclusively luxury or high-end housing stock being added to the market, and almost exclusively condo, rather than co-op.”

Miller agrees, “When I started working in the city back in the mid-80s, 85 percent of the housing stock was co-op and only about 15 percent were condos. In the ‘90s it was about 80 percent co-op and 20 percent condo. In the past decade it's about 25 percent of new development are condos, and the market is weighted towards much larger apartments.”

What is most interesting, or depressing, depending on your point of view is the vast differences in housing prices in thirty years. According to Miller, in the first quarter of 1989 the average co-op cost $376,393, and the average condo was $415,359. In the fourth quarter of 2012 the same co-op would cost $1,190,450 and the same condo would cost $1,867,576. Quite a difference.

In April 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported that co-op and condo prices reached an all-time high pointing to a pair of duplex apartments on the 12th and 13th floors of 740 Park Ave., a luxury limestone co-op building on the corner of East 71st Street which sold for a combined price of about $52 million, making it the highest ever paid for a Manhattan cooperative apartment. In January, the $88 million purchase by a Russian billionaire set a new record for condo sales. With an annual maintenance listed at about $412,000 a year (roughly the sale price of a typical Manhattan studio apartment) the Park Avenue apartments consist of 30 rooms, including eight bedrooms, 10 bathrooms and six terraces, and are linked together through two private elevator landings.

Although these numbers refer to the “trophy” co-op and condo sales in the market, the numbers indicate that they still affect the mid-level market as a whole. The current listing for a lower-floor duplex at 740 Park is priced at $23 million. The combined trends of new luxury construction and high end prices have returned New York City firmly back in its former glory as the millionaire’s playground that it once held back in the turn of the 20th Century.

So Where Do We Stand Today?

In the 1980s, New York was finally reaping the rewards of the legendary “I NY” campaign launched in 1977 to bring tourism back to the city. Ever since, tourism had been on the rise and today New York City remains the number one destination of overseas travelers to the United States.

By 2013, New York City had seen both the first African American mayor and President of the United States. In the 1980s, those events were merely the conjecture of fiction. And a futuristic society was only the stuff of Hollywood movies. Although 21st Century New York does not have flying cars, (many citizens do own hybrid electric) and we still don't have jet-packs, (darn it), but New York City does boast the world’s largest fleet of hybrid electric buses in use for public transport.

With new eco-friendly buildings rising in all five boroughs, spiraling towers reaching new heights, newly-designed tree-lined streets, skyrocketing rents and trendsetting billionaire residents, it’s plain to see that when in it comes to New York City, reality is often better than fiction.

J.M. Wilson is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment